As we previously mentioned, very little information has been preserved about anticult ideologues, their methods and connections. The data that could shed light on their activities is likely to be present in classified archives, inaccessible to the general public. This lack of access significantly limits the ability to study anticult influence and methods and leaves many aspects in the dark.

Nevertheless, researchers recognize that missionarism, or more precisely, anticultism, has been used as an important element in geopolitical strategies. Religious factors are among the defining elements that shape the identity of one or another civilization and, consequently, the geopolitical map of the world. Anticultists have influenced and continue to influence its formation, invisibly shaping the public mindset. Their activities are a form of exercising control and global manipulation over the collective consciousness and space.

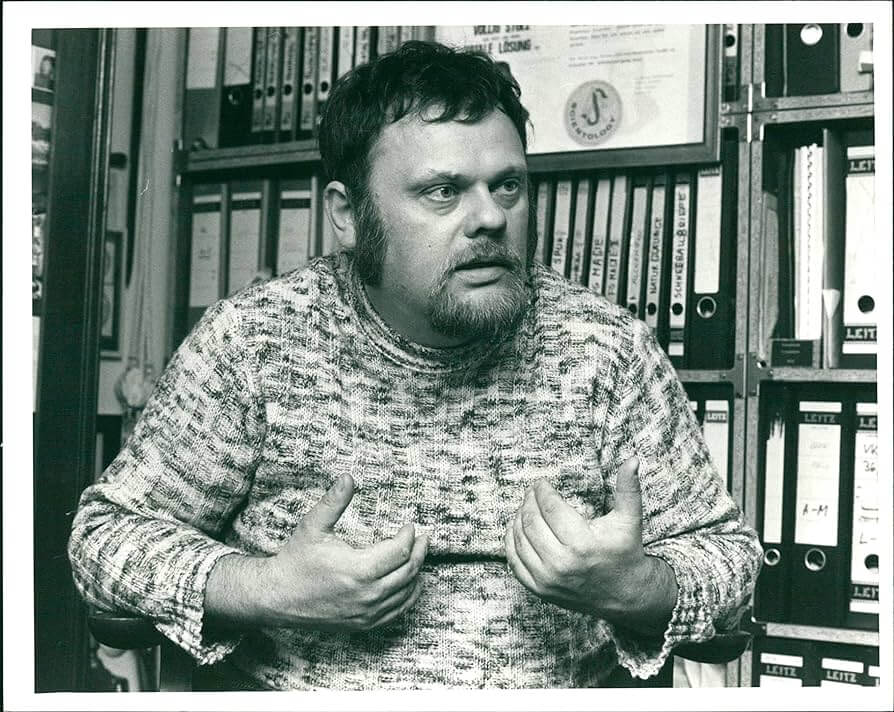

One of the most significant and shadowy figures of the second half of the 20th century was Friedrich Wilhelm Haack (1935–1991) 1, a German anticultist and Lutheran pastor. Haack is widely recognized as the chief ideologist in Europe’s fight against cults after World War II. Although biographical details about him are scarce, we will nevertheless attempt to provide some insight into his life.

From what is known, Friedrich Haack attended a gymnasium in Eisenach from 1950 to 1954 before working as a laboratory assistant at the University of Jena in 1954–1955. In 1955, he moved to the Federal Republic of Germany, where he studied journalism and theology in Heidelberg and Neuendettelsau from 1956 to 1961, obtaining a theology degree in 1962. From 1963 to 1965, he taught at preacher seminars in Hof (Saale), and in 1964, he was ordained as a pastor of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Germany. Between 1965 and 1969, Haack served as a pastor in Hof and joined the group Sects and Ideological Issues. In 1965, he founded the Working Group on Religious and Ideological Issues (Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Religions- und Weltanschauungsfragen, ARW) and the Evangelical Press association for Bavaria in Munich.

Haack led research expeditions to India (1981), Japan and South Korea (1984), and South America (1986).

His influence on the anticult movement was profound, with his books and public appearances playing a significant role in shaping public opinion on new religious movements (NRMs). By 1987, Haack had published 40 books, with a total of 700,000 copies sold. He wrote extensively for newspapers and magazines, frequently appeared on radio and television, and participated in seminars and international anticult conferences.

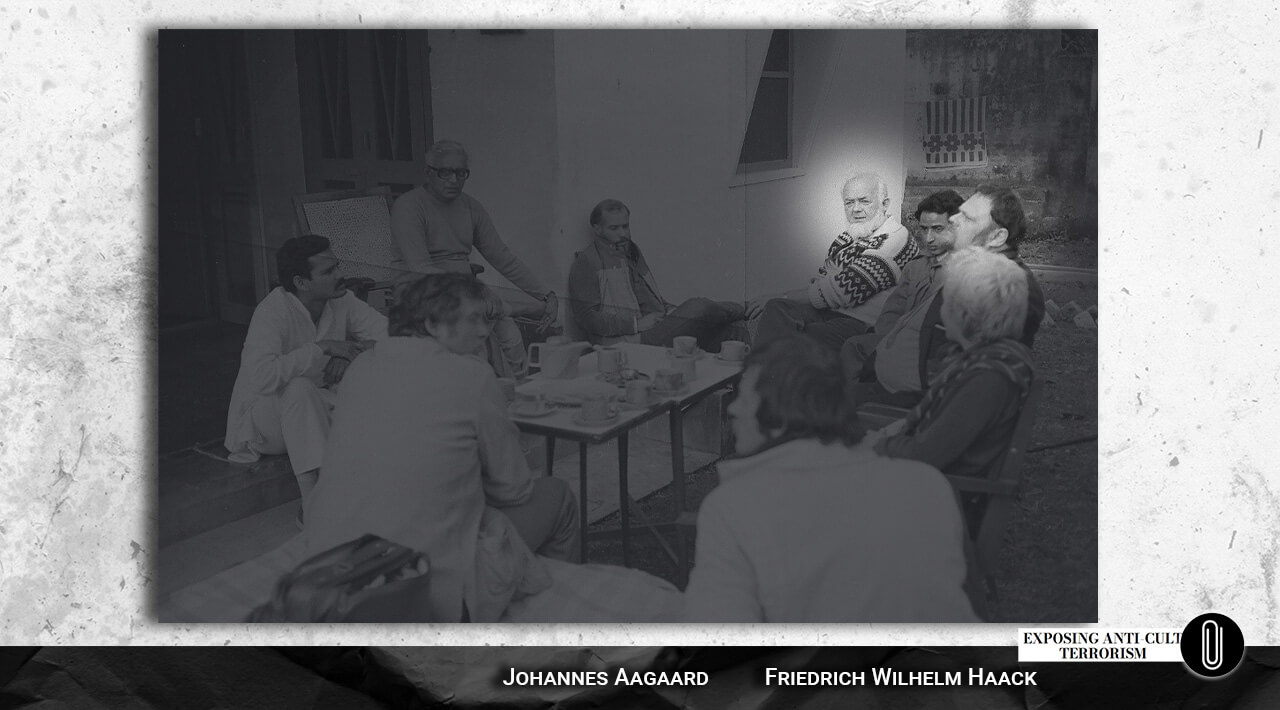

In 1973, Friedrich-Wilhelm Haack assisted Danish theologian Johannes Aagaard in founding the missionary theology institute Dialog Center (DC) and, in 1981, took part in establishing the Dialog Center International (DCI) 2, where he served as vice president.

In 1974, Haack gained recognition for coining the term “youth religions,” which he used as a synonym for NRMs, or “new religious movements.” In 1975, he founded the organization Elterninitiative (“Parents’ Initiative for Help against Mental Dependency and Religious Extremism”) which grew to include over 500 members. Elterninitiative’s primary activities included gathering and providing information about “sects” (Sekten), “youth religions” (Jugendreligionen), “guru movements,” and “therapy cults” (Psychokulte) — all new terms introduced by pastor Haack. 7

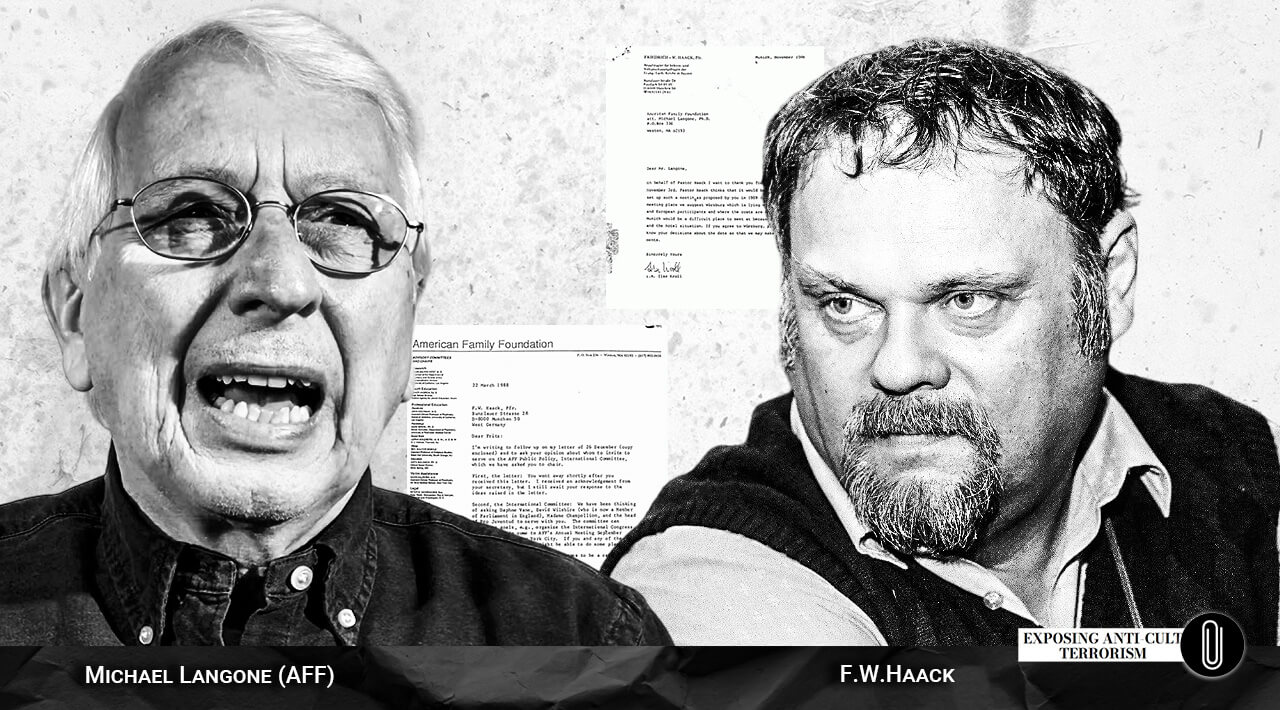

In 1985, Haack joined the Advisory Board of the American Family Foundation (AFF), a leading anticult organization in the U.S.

Up until his death, Haack conducted extensive apologetic work, exerted great influence on church life, and was one of the most influential critics of the NRMs among the German church representatives. Official records indicate that he maintained close ties with countercult organizations in Germany, the United States, the United Kingdom, Austria, France, Denmark, and Greece. Unofficially, the list of almost 30 countries participating in the Dialog Center International (DCI), where Haack served as vice president, illustrates the global scale of his collaborative efforts.

In his book Das Mun-Imperium, Friedrich-Wilhelm Haack explained the purpose of his work as follows:

“Everyone should form their own opinions. Yet, often, the process of forming opinions depends on the information available. This is especially true when it comes to beliefs shaped by those opinions. The materials and reflections presented here offer no more than a possible source for independent opinion-forming. Whether to accept them or not is up to the reader.” 1

Doesn’t it sound familiar? This sophisticated verbal tactic of evading responsibility for dehumanization and informational terror attacks is now successfully employed by Alexander Dvorkin, the leader of the anticult movement in Russia. This clearly confirms the succession of ideological fight methods through the generations. It’s worth recalling that Dvorkin was a disciple of Johannes Aagaard, who collaborated closely with Haack for decades. Such continuity of ideas reflects a deep connection among generations of anticultists who continue to use well-tested strategies for discrediting religious movements.

To further investigate the subject of continuity, it is worth turning to the pre-war and post-war events, which will allow us to trace similarities and identify historical parallels.

1921: The Apologetic Center

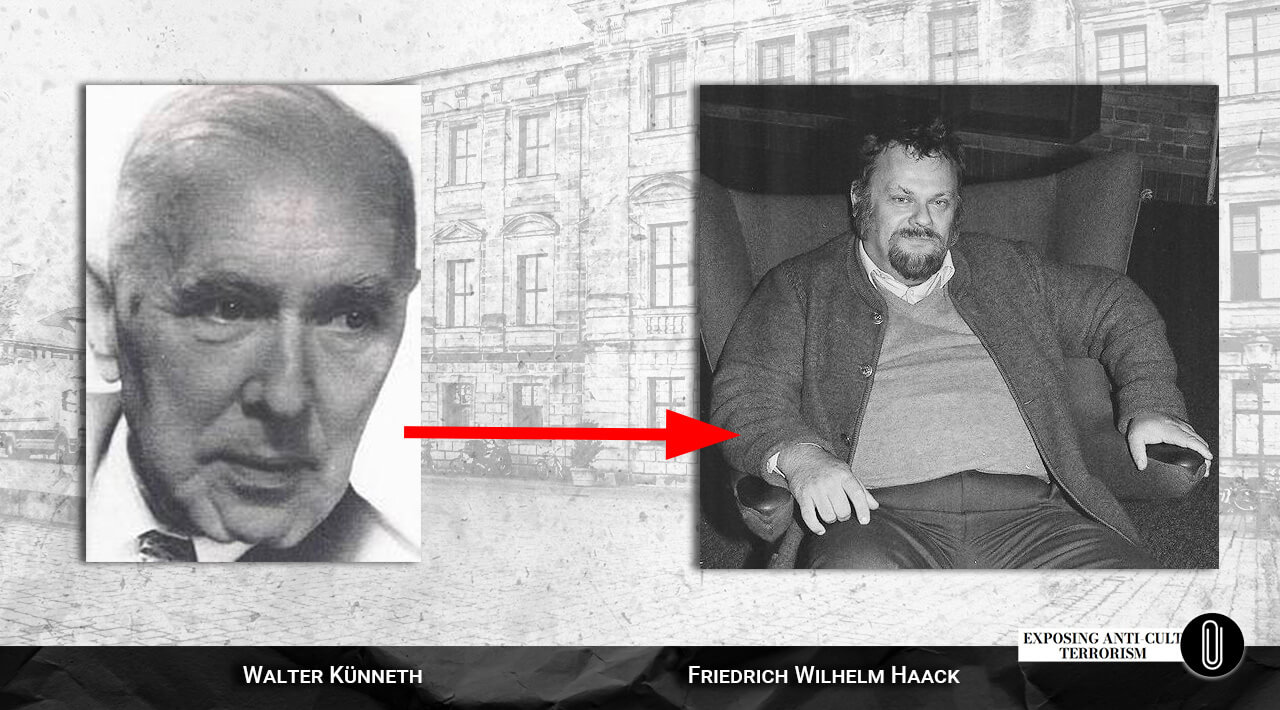

As we mentioned in our earlier articles, the Apologetic Center was founded in 1921 within the German Protestant Church. This center can be seen as a prototype for modern anticult organizations. Its leader, pastor Walter Künneth, became known for his anti-Semitic views. From the very beginning of his activity, Künnet actively opposed so-called “non-Christian trends”, which later formed the basis for the ideology of anticultist movements.

Initially, the Center functioned as a repository for collecting materials and information; it organized apologetic training, lectures, and publications in the specialized magazine Wort und Tat, dedicated to ideological fight issues.

Over time, the Apologetic Center expanded its activities by systematically collecting data on various religious and philosophical groups, and other associations. In 1930, the collected materials on “non-Christian” movements were arranged into an organized archive that covered a wide range of views deemed freethinking. This work culminated in 1932 with the publication of the guidebook “Freethinking and the Church,” aimed at combating organizations with dissenting positions.

The anticult activities of the Apologetic Center included opposition to movements like Anthroposophy, Darwinism, Monism, Spiritualism, and Occultism, which the Protestant Church viewed as their competitors. Lectures, articles, and other publications on these topics reflected methods that largely inherited the inquisitorial approach used by Martin Luther in fighting dissent.

1933 Collaboration with the Nazi Regime

Walter Künneth pursued the goal of eliminating religious minorities and, in 1933, openly supported Adolf Hitler’s initiative to “eradicate Jewish influence in public life.” This position drew the Gestapo’s attention to the activities of the Apologetic Center, whose methods of struggle were highly rated by the secret state police. The interest of the Gestapo was an indication to Künnet of the recognition of his work, which he mentioned approvingly in his report to the leadership of the Protestant Church of the Reich.

“The Gestapo expressed great interest in the Apologetic Center’s archive on sects, as well as our work against freethinking, Marxism, and Bolshevism. The Gestapo expressed a desire to lead the fight against illegal freethinking alongside the Apologetic Center in the future. The exchange of materials between the Gestapo and the Apologetic Center has already begun.” 3

With the start of the active phase, the Apologetic Center’s staff systematically provided materials on the political stance of various religious communities to the Reich Ministry of the Interior, the Propaganda Ministry led by Joseph Goebbels, and the Gestapo.

In other words, the Apologetic Center became a central reference point for Nazi authorities in determining which religious associations should be considered cults and a potential threat to state ideology. As a result, there were formed and constantly expanded the lists of so-called sects and cults – associations that the Apologetics Center considered dangerous to the state ideology.

In this way, the Apologetic Center, led by Walter Künneth, produced many slanderous pseudo-expert reports. These materials helped turn religious organizations, along with Jews, into targets of the Nazi dictatorship, leading to their brutal persecution, including sending members of these organizations to concentration camps. As historian Horst Junginger notes, “If in 1931 around 150 religious and non-religious ideological communities were registered and documented, by 1933 this figure had risen to around 250, and by 1936 the archive lists recorded around 500 groups and sects considered ‘dangerous.’” 4 And yet no one asked: dangerous in what way, and to whom?

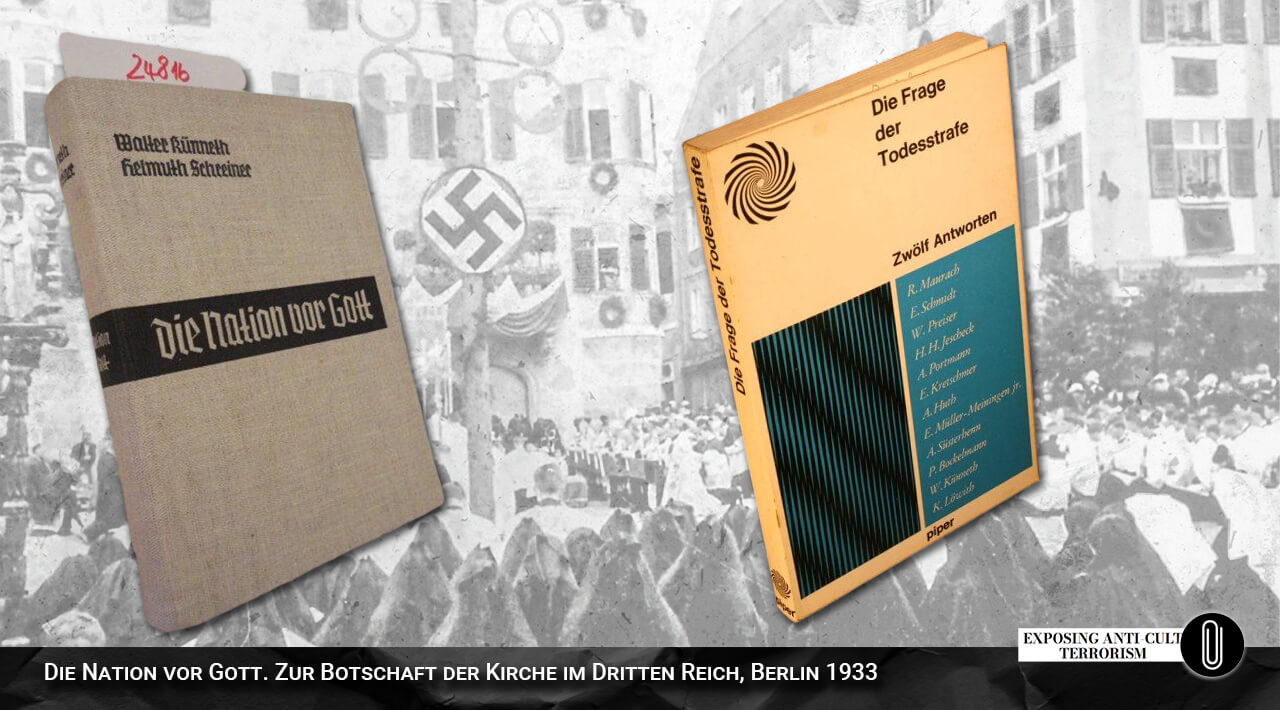

“Künneth followed Martin Luther’s teachings in at least two respects. In his work “The Nation of God: On the Church’s Message in the Third Reich” (Die Nation vor Gott. Zur Botschaft der Kirche im Dritten Reich, Berlin 1933), co-authored with Helmut Schreiner, he expressed his hatred for Jews. In the article ‘Theological Arguments for and Against Capital Punishment’ (Die theologischen Argumente fur und wider die Todesstrafe), published in the book The Question of the Death Penalty: Twelve Replies (Die Frage der Todesstrafe, Zwolf Antworten) Frankfurt am Main 1965), he advocates for capital punishment.

Künneth is considered one of the most influential conservative Evangelical Lutheran theologians of his time. Within the Evangelical Mutual Aid Society, there is a special academic division, the Walter Künneth Institute.” 8

It’s important to note that after the war, unlike many other Nazi figures, Walter Künneth was not convicted for his anti-Semitic views or cooperation with the Gestapo. Instead, he was awarded the Maximilian Order for Science and Art, as well as the Bavarian Order of Merit by the Free State of Bavaria. From 1946, Künneth held a professorship in Protestant theology at Bavaria’s University of Erlangen and received the honorary title of “Church Counselor.” 5

After the War

After the victory over Nazism, the international community established the United Nations to maintain and strengthen peace and protect human rights. Nevertheless, despite all enacted laws, in 1964, the German Protestant Church officially reestablished the church office of the Commissioner for Sects and Faith in the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Bavaria and appointed pastor Friedrich-Wilhelm Haack to the role.

Notably, the anticultist Haack studied Protestant theology in the Bavarian University of Nuremberg, precisely during the years when Walter Künnet was teaching there and held the position of professor in the department of Protestant theology. Haack later succeeded Künnet in promoting Nazi ideology and took a key position as the chief ideologue of anticultism in Europe. As a confirmation, one can examine an almost identical behavior strategy of the Apologetic Center in pre-war Germany and pastor Haack in post-war Germany: at the first stage their activities were limited to researching sects, allegedly for the purpose of collecting information, and at the second stage they began to fight them.

Haack stated that communities should be “known” “if the church wants to convey its message in this pluralistic society” and fulfill its mission. Yet, soon Haack made the following statement, “If we understand our faith correctly, we do not have the right to allow the “others” to continue in their faith…”

And the fight against dissent began once again. It was Haack’s initiative in the early 1970s that revived the Nazi-era term “Working Group on Religious and Ideological Issues”, adopting a nearly identical name for this division from the Nazis — “Department for Religious and Ideological Affairs”.

At Haack’s initiative, lectures and sermons on sectarians and their danger began again. Haack urged that Protestants and Catholics should view sectarians as beings devoid of human dignity. His sermons fueled hatred and contributed to a discord in German society. After one of his sermons, followers of a so-called sect faced threats and aggression. People shouted at them, “They should be lined up against the wall, in a row. Hang them!” and, “You should be hanged! Heil Hitler!” 6

In 1990, Haack compiled a “blacklist” of new religious movements, so-called sects and cults, which German authorities used as a reference for the next 16 years.

Analysis of the international anticult movement shows that its representatives, especially its leaders, maintain close ties and continue to cooperate despite the changes in the global political environment. For many years, all of them have been connected by one thread – the idea of apologetic fight.

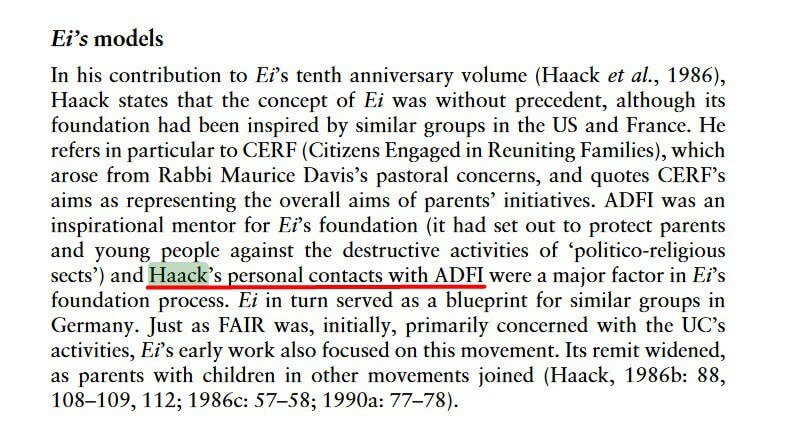

To reiterate, Friedrich Haack was the key figure of the second half of the 20th century. He served as the vice president of the Dialog Center International, collaborated with Johannes Aagaard, and was a research director at AFF (U.S.). Haack also worked closely with the British anticult organization FAIR. Elisabeth Arweck’s book, “Researching New Religious Movements: Responses and Redefinitions” 7, discusses these connections in detail.

![Screenshot from Elisabeth Arweck’s book “Researching New Religious Movements. Responses and redefinitions” by [7]](https://actfiles.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Screenshot_8.jpg)

The same book 7 provides evidence of close ties with the French anticult organization ADFI and the American CERF.

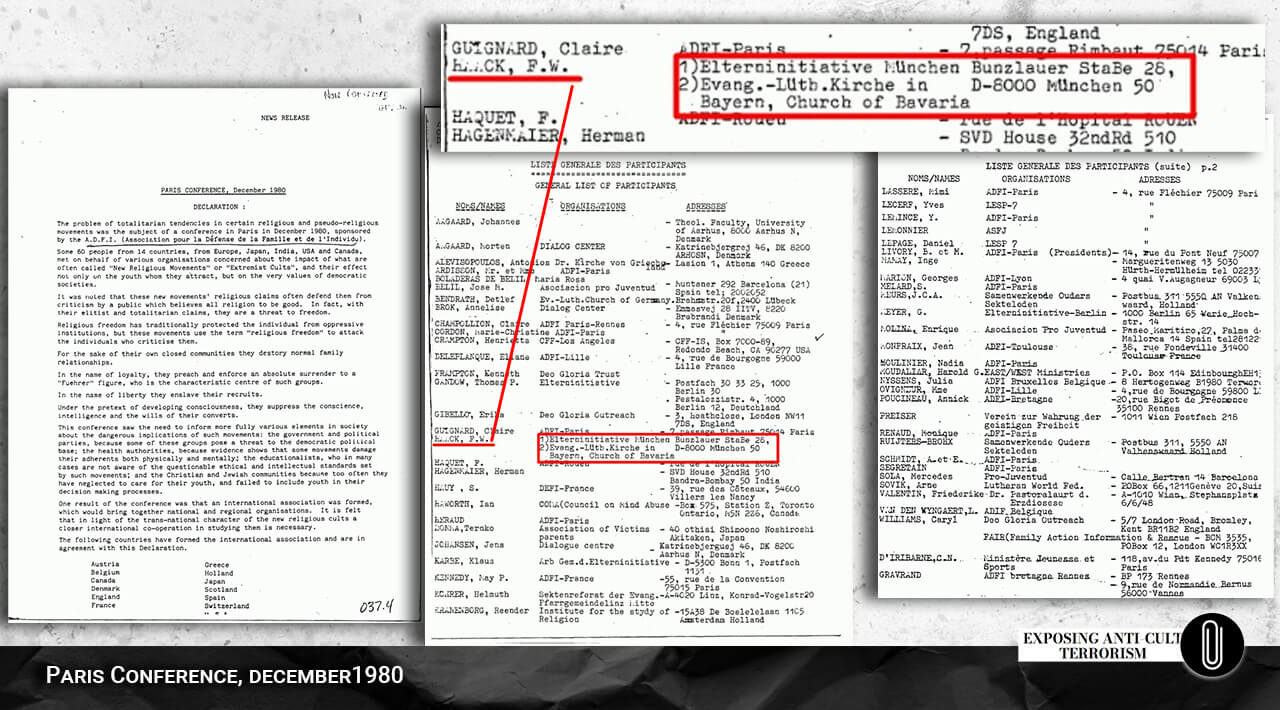

Haack was among the participants of the first international congress in Paris in December 1980 under ADFI’s auspices, where a decision was made to establish FECRIS 10.

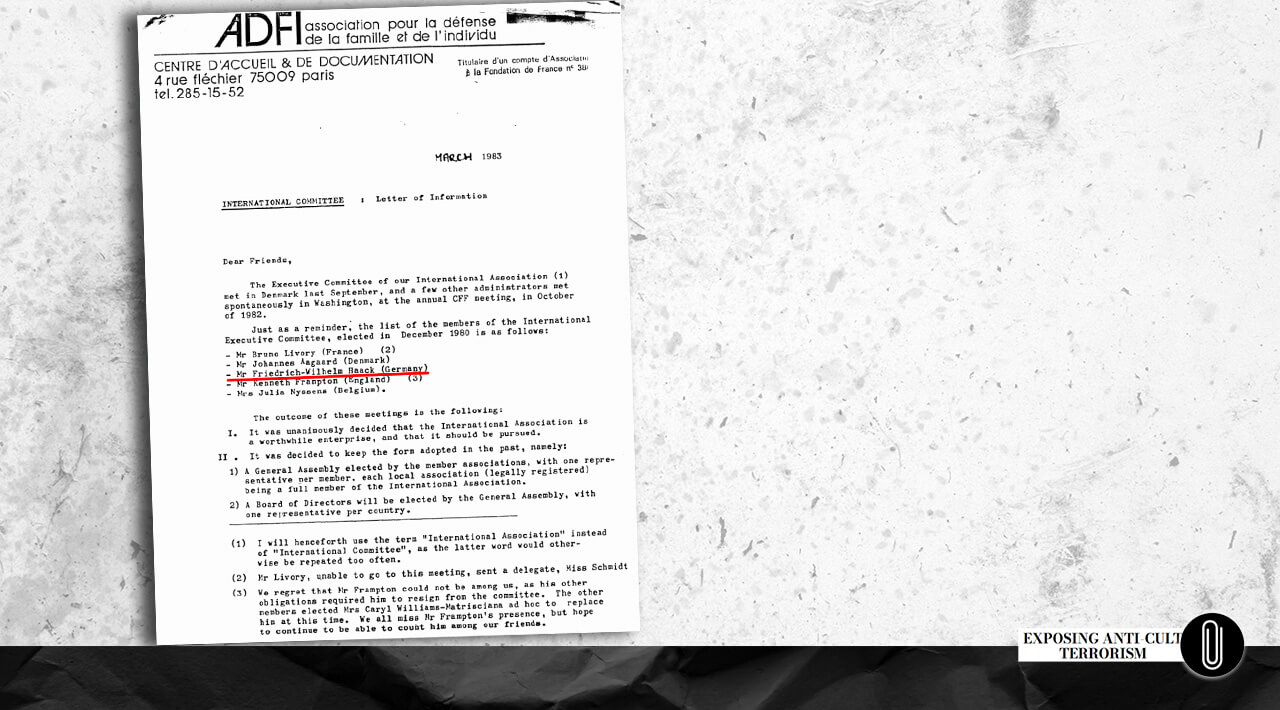

In October 1982, an executive committee of the international coalition, which was led by ADFI and included Haack, Johannes Aagaard, as well as representatives from France, England, and Belgium, arrived in Washington, D.C., to attend the annual CFF meeting. The aim was to discuss the establishment of an International Association for Coordinating Anticult Movements (ACM) with their American colleagues. The proposed structure was supposed to consist of a General Assembly, with each ACM member organization represented by one delegate, and a Board of Directors elected by the Assembly. They decided that future correspondence would be sent to AGPF in Germany, and the second international meeting was scheduled for October 1983 10.

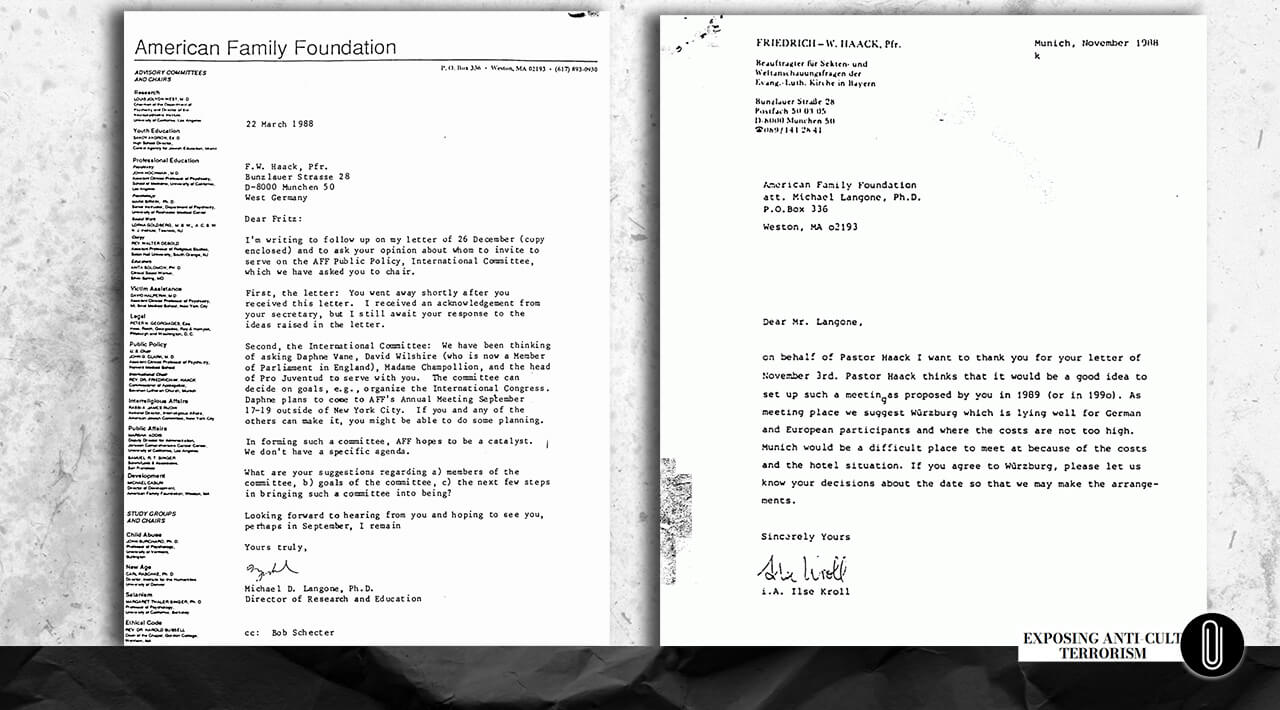

Haack’s correspondence with Michael Langone also points to close cooperation on unifying North American and European anticult efforts.

In a letter dated March 22, 1988, Michael D. Langone, a psychologist and director of research and education at AFF, wrote to Haack to discuss potential members for an International Committee on Public Policy at AFF, which Haack had been asked to lead. Langone suggested Daphne Vane (of England’s FAIR), a French woman from ADFI, a Member of the British Parliament, and the head of the Spanish Pro Juventud. This committee would be tasked with organizing the next international congress. Langone noted that Daphne Vane was a suitable candidate, as she was already planning to attend AFF’s annual conference, scheduled for the following September. In a reply, Haack’s assistant stated that Haack suggested Würzburg, West Germany, as the congress location.

Bertil Persson’s book The Fight Against Sects provides insight into the rise of anticult hysteria in Germany:

“During the chancellorship of Kohl, sweeping actions were taken against new religious movements (commonly called ‘sects’), including the establishment (influenced by Haack’s ideas) of an Investigative Committee on Sects, which operated from 1996 to 1998, and a staggering media-driven ‘witch hunt,’ with hundreds of articles weekly on ‘sects.'” 8

The Bundestag’s Investigative Committee on Sects and Psychogroups

Under the influence of Friedrich-Wilhelm Haack and his U.S. associate psychiatrists, the AGPF (Action for Mental and Psychological Freedom) was founded and shared office space with the movement “Mentally Ill.” Their ideas spurred a Bundestag (German parliament) initiative to create the “Enquete Commission on Sects and Psychogroups.” This committee was mandated to operate across four key areas:

- Analyzing the goals, activities, and practices of so-called sects and psycho groups active in the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG);

- Determining why individuals join these sects and psycho groups and why membership in such organizations has increased;

- Identifying the challenges faced by individuals both during their involvement and when attempting to leave these organizations;

- Developing actionable recommendations, considering ongoing societal debates on these issues.

One of the Commission’s “sect experts” was Bernd Abel, whose Nazi connections will be discussed later.

“The fact that today we have parliamentary oversight of sects along with official anticult activists at the church, community and political levels is a result of Haack’s apologetic work. It is precisely Haack’s ideas that inspired the Christian Social Union (CSU) in Bavaria to push for a “blacklist” of certain individuals and new religious movements in the context of the implementation of the Schengen Convention in 1990. On November 9, 2006, hearing a court case initiated by the Unification Church, the German Federal Constitutional Court ruled that libel was used against sects.” 8

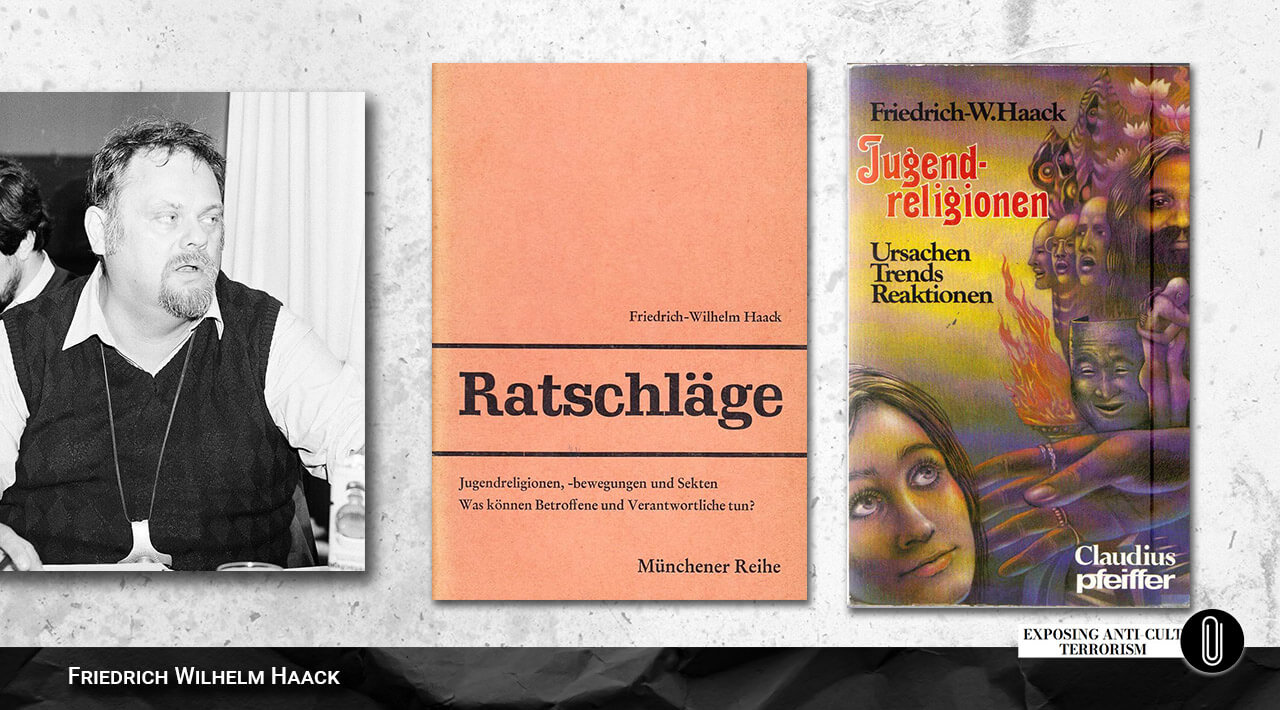

Haack laid out his anti-sectarian program in publications such as Advice. Youth religions – movements and sects. What can victims and authorities do? [Ratschläge. Jugendreligionen — Bewegungen und Sekten. Was können Betroffene und Verantwortliche tun?] Munich 1977), and Youth Religions. Causes. Trends. Reactions (Jugendreligionen. Ursachen. Trends. Reaktionen) Munich 1979.

He classified as “youth religions” groups like Ananda Marga, Osho’s Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh movement, Children of God, Church of Scientology, Divine Light Mission, Hare Krishna movement, Transcendental Meditation, the Unification Church, and many others.

However,

“Haack’s apologetic fervor was not only directed at ‘youth religions’ but also Muslims, the Catholic Church (mainly the Jesuits and *Opus Dei), and secret societies. Meanwhile, he was himself a member of the Masonic Lodge of Rose of Seven Seals and in 1982 received the Bernhard Mayer’s Medal from the United Grand Lodge of Germany!” 8

He held the view that his own congregation had failed in the task of defending the Christian faith, and so he, as a pastor, saw it as his mission to carry out that task. Therefore, he rejected all authorities, including universities and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

“Tolerance towards the indifference that, allegedly, everyone is blessed in their own faith is ultimately offensive to faith itself.” (Sects, Munich 1974). In his fanatical endeavors, he resorted to deprogramming, manipulation, and defamation, which led him to face — and lose — several court cases.

“…we do not have the right to allow the “others” to continue in their faith…”

We often wonder why the world is so cruel and unfair. Part of the answer is that history is a deceitful thing. It is written by victors and anticultists. Why? Because religions are as old as anticultism is. Everything is much more serious than you think. Apologists, inquisitors, missionaries, sect-fighters, anticultists – this punitive force has always been hiding under the cover of monastic cassocks and temples, acting cunningly, cruelly and ruthlessly. It has always been astonishing to see the unimaginable degree of authority bestowed upon them by someone that allowed them to punish, rampage and alter the course of historical events.

Before “The IMPACT” documentary and our project “Exposing Anti-Cult Terrorism”, finding any compromising information on Haack seemed almost impossible. As Belarusian sectologist Martinovich wrote in his work on the history of the Dialogue Center, anticultists do not put their archives on public display. The activities of religious missionaries remain unexplored and often misunderstood. Haack, a pastor and missionary who saw himself as the ideological heir to the Inquisitors, firmly believed in the righteousness of his ideological fight against dissent and devoted his life to it. He wielded enormous influence in circles whose decision could fundamentally change the course of history. They knew it, we didn’t. While they implemented their far-reaching plans, we suffered the consequences and dealt with devastation and casualties. And each time we asked ourselves: why is the world so cruel and unfair?

What ideas did the anticultists bring to the world? They raised themselves on the pedestal of the chosen ones, proclaiming their exclusivity and believing themselves to be the bearers of the supreme truth, which, according to their claims, grants eternal life. Their unshakable faith in their chosenness was backed by impunity.

At first, they walked proudly, arrogantly and gloriously, believing that the banner of truth was leading them. But this path was paved with heads, bones, and broken destinies. Their fight was justified only by a fanatical faith elevated to the rank of sacred duty. Ancient “holy writings” and apologists who had long since fallen into oblivion served as their shield, behind which they hid terrible grief and suffering that sprouted abundantly on the soil of the delusions they had sown.

But you only have to look at their faces and catch that strange, demonic look in their eyes to realize that anxiety is raging within them, as if some diabolical madness has taken them captive. And this madness, never releasing them, takes away their peace. It deprives them of a chance to find peace in this life and leaves no hope for comfort in the promised afterlife.

Their faith, their so-called “holy truth”, is like an invisible mental clot, drifting through the minds of each new generation of “chosen” fanatics across the millenia. This continuous idea is passed on like a relay, one that is able to radically distort reality. It’s like an incurable illness, turning those infected against their neighbors, driving them to sow discord and intolerance.

It is akin to madness, but one that allows its bearer to remain on the edge of sanity without crossing the threshold of socially acceptable behavior. Apologists, inquisitors, missionaries, anticultists, and sect-busters are transmitters of a deadly plague that destroys society from within and wreaks havoc. Ideology they bring leaves ruin in its wake.

Künneth — Haack — Aagaard — Dvorkin… Who’s next?

Sources:

1. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Friedrich_Wilhelm_Haack_(Theologe)

2. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dialog_Center_International

3. https://theologe.de/theologe4.htm

4. https://publikationen.uni-tuebingen.de/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10900/94079/Junginger_026.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

5. https://theologe.de/theologe4.htm#Ausschaltung

6. https://taz.de/Hettstadt-betr-quotEin-Dorf-kaempft-gegen-das-Universelle-Lebenquot-taz-vom-1489/!1815658/

7. “Researching New Religious Movements. Responses and redefinitions”, Elisabeth Arweck

8. Bertil Persson’s book “The Struggle Against Sects: Ideological Foundations and Their Failure”

9. Ubersicht die Sekten und Weltanschauungsarbeit, 1. Halbjahr 1970)

10. https://www.cesnur.org/2001/CAN1.htm