Introduction

Between the 1960s and 1970s, the USSR continued its active fight against religion, which was considered a “relic of the past.” The Soviet government restricted the activities of believers through repressive measures. The Council for Religious Affairs and its representatives deliberately hindered the emergence of new priests, especially those who were educated, thoughtful, and genuinely committed to serving. While religious services were formally permitted, any activity outside the church, including personal interactions between priests and believers, was strictly prohibited.

Over time, as the older generation, those who remembered church life before the revolution, passed away, a distorted perception of religion became entrenched in public consciousness. Faith and church life came to be seen as mere participation in rituals within the church, while the daily lives of believers became increasingly confined to ordinary mundane concerns. Instead of a holistic blend of faith, behavior, and spiritual convictions, the sole criterion for religiosity became the external act of attending church services.

In the 1980s, the fight against religion continued in the country. The Soviet government maintained total control over the church. KGB officials closely monitored the content of sermons delivered in churches, tracked personal connections, continued to shut down churches, and prevented youth from participating in services. All prominent church figures were in the service of the KGB, while those who attempted to act independently had their “oxygen cut off” — they were sent to labor camps or psychiatric hospitals, dismissed from their jobs or educational institutions, and subjected to other forms of pressure.

After the fall of the atheist regime in the Soviet Union, people turned to religion in search of spiritual answers to eternal questions. Churches were being restored and opened. Many previously forbidden topics became open for discussion, and people could openly express interest in faith and the Church. However, the level of pastoral training remained low, and spiritual education for laypeople was virtually nonexistent. The Church faced the urgent task of educating millions of people who were coming to churches in the basics of Christian faith, prayer, and religious life. At the same time, the activities carried out by the KGB did not cease. Individuals pursuing non-church interests began to act in the name of the Church, with no concern for fostering trust or unity in society. Taking advantage of the lack of religious education among believers, they succeeded in portraying traditional Church practices as distortions, while introducing substitutions into Orthodoxy that were accepted as the norm. Pastors who focused their efforts on preaching the Gospel, educating, and uniting people became inconvenient.

In 1990, Russia adopted the law “On Freedom of Conscience and Religious Associations.” It proclaimed the equality of all religions before the law and affirmed the right of every individual to freely choose, practice, or not practice any religion. The law guaranteed the separation of Church from the state and schools, as well as prohibited state interference in the affairs of religious organizations. This law was a significant step toward ensuring religious freedom after decades of state-enforced atheism in the USSR. It marked a new stage in the country’s development — Russia entered an era of liberal change.

“But something changed ‘in the air,’ so to speak, in our country after October 1993. And apparently, this influenced the opinion of Patriarch Alexy II…” said Father Georgy Kochetkov. 1

In previous articles, we have repeatedly emphasized the decisive role of Alexander Dvorkin in the events that unfolded in Russia. In this article, we would like to show how he managed to create an inquisition tool for suppressing dissent — both outside and within the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC) — in a country that once had a chance for normal democratic development. This article will explore persecutions within the ROC.

Alexander Dvorkin’s Return to Russia

We have carefully studied Alexander Dvorkin’s biography, and in our view, certain aspects vividly illustrate how skillfully he managed to gain the trust of many people and shape events in a way that made them appear natural, without any external influence. Here is what Dvorkin himself says about his return:

“When I returned to Russia [1991] with the blessing of my now-departed spiritual father, Father John Meyendorff of blessed memory, I began working in the newly established Department of Religious Education and Catechism of the Moscow Patriarchate. Father Gleb Kaleda, to whom I was assigned, became my next spiritual father. 2

Father Gleb almost immediately suggested that I take on the subject of sects. I replied that I was a Church historian, and sects are an ahistorical concept unrelated to Church history. ‘Besides, I know nothing about sects!’ I said. ‘No, you do!’ Father Gleb retorted. ‘Sects come from the West, so unlike us, you’ve at least heard something about them there. Besides, you know foreign languages. And your academic background will help you gather information, process it correctly, and present it competently.’” 3

Whether this conversation with Father Gleb actually took place or not is impossible to verify, as Gleb Kaleda passed away in November 1994.

However, it is important to note that Dvorkin identifies this meeting as the beginning of his fight against sects and cults. The story is framed as if Dvorkin was persuaded to take on this work. “Sects came from the West,” and “by a fortunate coincidence,” at the same time, the very person “from the West” arrived in Russia — someone who was already familiar with the concepts of sects and cults and possessed the necessary skills: knowledge of languages and religious education. The perfect candidate!

The timing of his arrival is also significant. Dvorkin came at a moment when the old church system had collapsed, and there was a pressing need to form a new one. From Dvorkin’s biography:

“He did not, however, return to a ‘void.’ It was at this time that the Department of Religious Education and Catechism began to be established within the Moscow Patriarchate, headed by the renowned Byzantinist, Hegumen Ioann (Ekonomtsev). Father John Meyendorff was aware of this and prepared a recommendation for Alexander Leonidovich to join this very structure. Thus, in March 1992, Dvorkin became a full-time employee of the religious education sector of the new department, led by Archpriest Gleb Kaleda.” 4

Another key point here is that all of Dvorkin’s subsequent activities were, in one way or another, tied to education and teaching, that is, the training of new church personnel who would be guided by Dvorkin’s ideas and those of the global anticult network, spreading them further to the masses.

The Establishment of the First Anticult Center in Russia

Dvorkin then recalls:

“Father Gleb began inviting me to meetings with distressed relatives whose loved ones had ended up in sects. That was when I first heard about the ‘Bogorodichny Center’ sect. During one of these conversations, I casually mentioned that the ‘Bogorodichny Center’ closely resembled the early Christian sect of the Montanists. At that point, the relatives of a person who had joined the Bogorodichniks asked me to accompany them to the mayor’s office and act as an expert. Similar requests followed afterward.” 3

Notably, religious scholar A. N. Leshchinsky classifies the ‘Bogorodichny Center’ as a religious organization associated with Orthodoxy but not under the jurisdiction of any local Church, making it an alternative movement. He concludes his study with the statement: “The Orthodox Church of the Sovereign Mother of God represents the Bogorodichny movement in Russian Orthodoxy.” 5

In essence, the persecution of the ‘Bogorodichny Center’ began precisely because it was not under the jurisdiction of the Russian Orthodox Church.

Dvorkin recounts:

“Gradually, journalists covering the topic of sectarianism began to take an interest in me. That was when I decided to organize a conference to explain to people who the ‘Bogorodichny Center’ adherents were and, if possible, put an end to the issue. The conference was held at Moscow State University [MGU], where I was then teaching church journalism in the Department of Journalism. It was there that I met my future spiritual advisor — Father Alexei Uminsky, who at the time was serving in Kashira and was in the process of conquering a church from one of the leaders of the ‘Bogorodichny Center.’ Incidentally, it was at this same conference that I first used the term ‘totalitarian sect,’ which seemed self-evident to me. I had no idea that I was the first to use it in Russian.” 3

“The conference took place, but it only raised more questions. Journalists continued to reach out to me, but now they were asking about more than just the ‘Bogorodichny Center.’ I had to turn to my American connections and ask my acquaintances in the U.S. to send me relevant literature. It became clear that if I was going to engage in this work, I needed to do it professionally.” 3

And this is where the Lutheran anticultist priest from Denmark, who had great affection for the Russian Orthodox Church, enters the scene:

“In the spring of 1993, Danish professor Johannes Aagaard came to Russia. By that time, he had already spent nearly 30 years actively opposing sects in Europe and around the world, earning the strong resentment of sectarians. He was a Lutheran, yet he had deep respect for the Russian Orthodox Church. When he saw the powerful wave of sects flooding into Russia, he immediately came to our country to offer his help in countering these organizations. He started asking who was working on this issue, and he was sent to me. I clearly remember our first meeting. We sat on fallen logs near one of the closed churches of the Vysoko-Petrovsky Monastery and had a long conversation about the problem. At the end, he invited me to Denmark so I could see how the research and apologetic Dialog Center, which he headed in Aarhus, operated.” 3

And this is how Dvorkin’s “knowledge” base began to take shape, laying the groundwork for future guilt-by-association accusations against any targeted group:

“For several years, I traveled to Denmark for events organized by the Dialog Center, and each time, I returned with a suitcase full of photocopied documents. These became the foundation for the archives of a similar organization in Russia — the Center for Religious Studies in the name of Hieromartyr Irenaeus of Lyons — the first sectologist of the Holy Church.” 3

The establishment of the first anticult center in Russia followed a decades-worn formula, showcasing the characteristic methods of anticult activists.

It all began with appeals from so-called “concerned parents,” whose children were members of a religious group — in this case, the “Bogorodichny Center.” Based on their accounts and with active support from the media, which fueled anticult hysteria, a public demand for combating “cults” was created. This activity was accompanied by conferences and public events dedicated to the issue of sects (cults), further increasing pressure on religious groups. According to Alexander Dvorkin, the creation of such a center was a conscious necessary step.

The same formula was used to establish organizations like the Parents Committee to Free Our Sons and Daughters from the Children of God (FREECOG), the American Family Foundation (AFF), the German Elterninitiative (‘Parents’ Initiative for Help against Mental Dependency and Religious Extremism’), the French ADFI (‘National Union of Associations for the Protection of Families and Individuals’), and many other anticult cells around the world.

Ultimately, on September 5, 1993, the Center for Religious Studies in the name of Hieromartyr Irenaeus of Lyons was opened, becoming the hub of anticult activity in Russia.

It is worth emphasizing that at that time, in 1993, two major anticult organizations were operating in the United States: the American Family Foundation (AFF) and the Cult Awareness Network (CAN), the latter scandalously infamous for its crimes against individuals. During CAN’s existence, Alexander Dvorkin maintained ties with the organization. In 1994, he organized an “anticult” seminar, inviting Ronald Enroth, a CAN member, as a speaker. 6 After CAN was dissolved in 1996 due to bankruptcy following numerous lawsuits, Dvorkin began denying any connections to the organization.

From Dvorkin’s biography:

“Just a year after the creation of the Center [the Center for Religious Studies], its work began to yield tangible results. Thanks in large part to Alexander Leonidovich [Dvorkin] and Deacon Andrey Kuraev, the Bishops’ Council of the Russian Orthodox Church adopted the resolution ‘On Pseudo-Christian Sects, Paganism, and Occultism’ in December 1994, which declared the ROC’s position on a number of destructive cults.” 4

Here, we want to highlight the particularly intense activity of anticultists in producing an enormous amount of various ‘anti-sectarian’ literature — books, articles, and their own ‘scientific’ works. In the vast majority of cases, these ‘works’ are not the result of original research, like those of religious scholars, but rather reprints and translations of other anticultists’ writings, with only minimal additions of their own ‘fresh’ thoughts, personal judgments and characterizations. This allows us to trace how openly Nazi ideas managed to penetrate and take root in the fertile soil of post-Soviet society.

Infecting Russian Society with Nazi Ideas

In 1992, the administration of Lomonosov Moscow State University (MSU) took note of the growing number of Orthodox publications in the country. This led to the idea of creating a church journalism group within the Faculty of Journalism, where Alexander Dvorkin was invited to lecture on church history. He was formally hired as a professor, despite not holding a professorial title. He developed a specialized course for students, which later became the foundation for his book “Essays on the History of the Universal Orthodox Church.” However, by the end of the second semester in 1994, the faculty leadership lost interest in the group and announced to the lecturers that it would be disbanded.

In that same year of 1994, Dvorkin moved to the newly established Russian Orthodox University of St. John the Theologian (RPU).

It is worth noting that the Synodal Department of Religious Education and Catechism, where Dvorkin worked, was also a co-founder of RPU, which was created in 1992. This university functions as an educational and research institution aimed at training specialists in secular professional fields, all while being rooted in the spiritual tradition of the Russian Orthodox Church.

In 1995, Alexander Dvorkin took the position of Head of the Department of Sect Studies at the St. Tikhon’s Orthodox Theological Institute (PSTBI), now known as the Saint Tikhon’s Orthodox University of Humanities (PSTGU). 4 That same year, he published a pamphlet titled “Ten Questions for an Intrusive Stranger, or Rules for Those Who Do Not Want to Be Recruited,” which is essentially a translation of a chapter from a book by CAN deprogrammer Steve Hassan.

“By that time, I had gathered enough material to write a monograph,” says the “professor.” “But the goal was different — to warn people about the threat of sects in simple language, in a booklet that could be read in an hour or an hour and a half.” 4

This pamphlet was published by the Moscow Patriarchate’s Department and was approved by the Moscow Patriarchate’s Publishing Council.

In that same year, 1995, Bishop Tikhon (Emelyanov) of Bronnitsy was appointed chairman of the Publishing Council and chief editor of the Moscow Patriarchate Publishing House. Following the collapse of the USSR, he took on the task of reviving the publication of the “Journal of the Moscow Patriarchate,” increasing its circulation to 10,000 copies by 1996. However, it was Alexander Dvorkin who introduced a particularly notable element to the publishing house’s activities.

Starting in 1998, the informational and educational magazine “Prozrenie” [“Insight”] was launched as a supplement to the “Journal of the Moscow Patriarchate.” This publication was dedicated to combating new religious movements and their followers. The materials for “Prozrenie” were prepared by the Center for Religious Studies in the name of Hieromartyr Irenaeus of Lyons, with Dvorkin serving as its deputy editor-in-chief.

Another member of the “Prozrenie” editorial board was Archpriest Alexander Novopashin, a close associate and student of Dvorkin, who headed the Novosibirsk regional branch of the Irenaeus of Lyons Center.

In essence, this magazine became another platform for Dvorkin’s anticult propaganda. Published twice a year until 2002, it was actively used to demonize alternative religious movements.

Following the release of the pamphlet “Ten Questions for an Intrusive Stranger,” by 1996, Alexander Dvorkin had participated in 14 conferences on totalitarian cults, published around 60 articles on the topic, and given no fewer than 30 interviews.

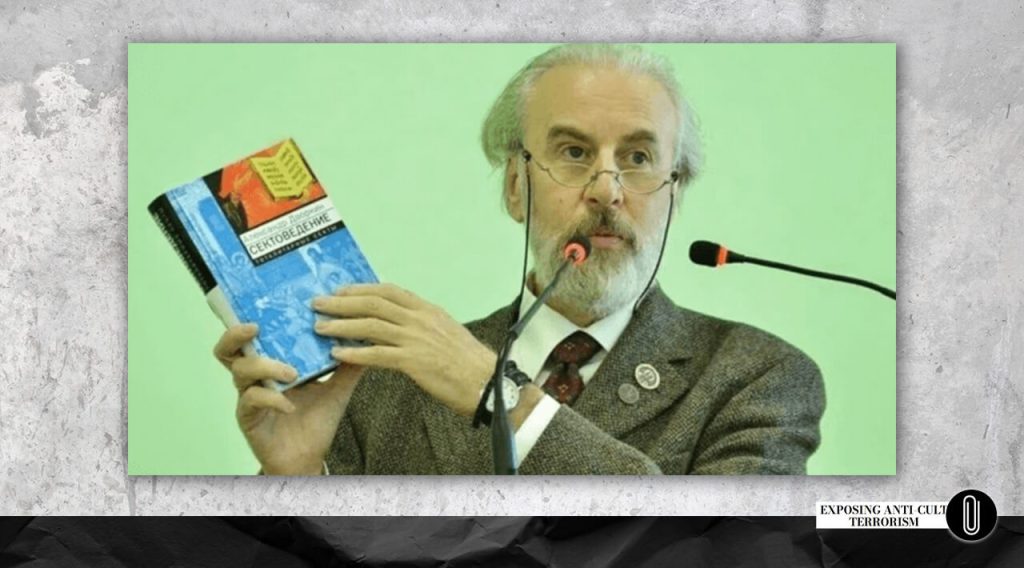

By 1998, Alexander Dvorkin’s book “Introduction to Sectology” was published, bringing him nationwide recognition.

“Actually, it was a learning guide for the ‘Sectology’ course, based on transcripts of my lectures at St. Tikhon’s Orthodox Theological Institute. But this book was probably the first to provide an overview of all the major sects operating across Russia. As a result, the ten-thousand-copy print run sold out in just three months.” 4

Such an active promotion of the anticult agenda, along with popularizing the rhetoric of a “sectarian threat” through conferences, publications, and collaboration with church authorities, quickly bore fruit.

1997: a new law “On Freedom of Conscience and Religious Associations” was adopted. This law marked the beginning of restrictions on religious freedom in Russia. Its key provisions included:

- The law introduced a division of religious organizations into “traditional” and “non-traditional.” It recognized the special role of “traditional” religions (Orthodoxy, Islam, Buddhism, and Judaism) in the history and culture of Russia, granting them certain privileges.

- New or “non-traditional” religious organizations faced strict registration requirements, including the need to prove their existence for 15 years, creating discrimination against them and depriving them of equal rights and opportunities.

- The state effectively began supporting “traditional” religions, especially the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC), strengthening their influence in public and political life.

The leadership of the Russian Orthodox Church highly valued the growing activities of Alexander Dvorkin and his Center. In his address at the annual Moscow Diocesan Assembly on December 23, 1998, Patriarch Alexy II of Moscow and all Rus’ emphasized:

“It is gratifying to note that during the preparation of the new law ‘On Freedom of Conscience and Religious Associations’ and after its adoption, antisectarian work in our Church has intensified. More conferences on this pressing topic are being held, and more parishes and deaneries have begun inviting Orthodox specialists to speak to them and convey necessary information to the clergy and active laity of our Church. It is also a good sign that local administrative bodies, as well as military units and other state institutions and educational establishments, have started inviting Orthodox experts on sectarianism more frequently. Particularly noteworthy in this process is the role of the Information and Consultation Center for Religious Studies in the name of Hieromartyr Irenaeus, Bishop of Lyons.” 4

With this statement, the Patriarch made it clear that Dvorkin’s activities played a direct role in justifying the need for the new anticult law and its practical implementation. By fueling antisectarian hysteria, Dvorkin’s work contributed to shaping the public and political climate in which restrictive measures against religious organizations were perceived as justified and timely.

At the same time, the activities of anticultist Alexander Dvorkin, while approved by the leadership of the ROC, have caused significant harm both to Orthodoxy itself and to society as a whole.

Here is how Igor Kolchenko, Co-Chairman of the former World Russian People’s Council, characterizes Dvorkin’s work:

“As a teacher at educational institutions of the Russian Orthodox Church, lecturing future Orthodox pastors, theologians, and scholars, A. L. Dvorkin undoubtedly harms the interests of the Church and the Orthodox people in Russia through his activities. He accustoms students to disregard scientific methods, encourages a superficial familiarity with the topic of religious sectarianism, and fails to form a canonical ecclesiastical perspective on this subject. Unable (or unwilling) to work in his chosen field professionally from a scholarly standpoint — that is, as the subject of modern religious sectarianism demands — A.L. Dvorkin produces overconfident amateurs for the Church through his textbooks. These individuals will not only fail to defend the interests of the Church in modern civil society but will also discredit church scholarship in the eyes of secular researchers, and the leadership of the ROC hierarchy in the eyes of society and the state.” 7

The introduction of inquisitorial anticult ideology into the Russian Orthodox Church not only discredited it in the public eye but also seriously undermined the foundations of religious ethics, distorting its original principles. This process has fueled internal conflicts, eroded the trust of believers, and disrupted church unity, turning into a tool of manipulation and pressure incompatible with true Christian values.

This opinion is shared by Igor Kanterov, PhD, a religious scholar and professor at the Institute of Advanced Studies at Moscow State University. In 2001, he wrote:

“The fundamental difference between secular schools of religious studies and those involved in anticult movements is that we — representatives of secular religious studies and our international colleagues — work in direct contact with the subjects of our research. Our goal is to understand them before passing judgment. In contrast, the main goal of anticult movement representatives is to condemn and find louder terminology and concepts to denounce them.” 8

Here is how Dvorkin himself describes the results of his activities and the effectiveness of this specific strategy in undermining the ROC:

“On the one hand, public consciousness today [2015] is more antisectarian, that’s true. However, while in the early 1990s the Church had a great deal of public trust, now there is a powerful anti-Church campaign underway, as a result of which many people begin to view everything coming from the Church as something dishonest or wrong — saying, ‘the religious folks are just taking out their competitors.’ But in this case, it’s actually easier to work because I’m not a clergyman but a layperson, and my explanations of what Orthodox faith is, what the Church is, and why one should be wary of totalitarian sects may appear more convincing to those critical of the Church than the words of a priest.” 9

This strategy apparently suited his employers quite well. In 2005, Alexander Dvorkin was awarded the Order of St. Innocent of Moscow.

The “Church Spring” of the Early 1990s

As we have already noted, much of Dvorkin’s “professorial” activities took place within the walls of St. Tikhon’s Orthodox University of Humanities (PSTGU). To understand the broader picture, let’s examine who founded this university, how it was established, and what consequences followed.

The history of the St. Tikhon’s Orthodox University of Humanities (PSTGU) is tied to the end of persecution and the beginning of the revival of church life. Radical changes were occurring rapidly: the restoration of parishes and monasteries, the glorification of saints, and the revival of active parish life, as well as educational, social, and missionary work. All this was accompanied by enthusiasm, joy and readiness for spiritual endeavors, leaving an image of “church spring” in the memory of the participants.

The first pages of PSTGU’s history date back to the early 1990s. On February 6, 1991, Theology and Catechism courses began operating in Moscow. These were preceded by a spiritual and educational lecture series initiated by Archpriest Dimitry Smirnov in the late 1980s.

According to the recollections of the courses’ secretary, Irina Shchelkacheva, the initiative group that developed the idea included priests Vladimir Vorobyov, Dimitry Smirnov, Gleb Kaleda, Sergey Romanov, and Arkady Shatov (now Bishop Panteleimon):

“They most often gathered in the parish house of Father Dimitry Smirnov. Professor Archpriest Gleb Kaleda was elected rector of the courses. Thanks to his efforts, premises for the courses were allocated at the Bauman Moscow State Technical University.” 10

The first academic council of the courses included Archpriests Valentin Asmus, Vladimir Vorobyov, Nikolai Sokolov, Sergey Romanov, Alexander Saltykov, Dimitry Smirnov, and Arkady Shatov, as well as Professors Nikolai Emelyanov and Andrey Yefimov.

In the spring of 1991, Father Gleb was invited to work in the Synodal Department of Religious Education and Catechism, where Alexander Dvorkin would later join on the recommendation of John Meyendorff. Due to his new role, Father Gleb requested to be relieved of his duties as rector of the courses, and on May 29, 1991, through a secret vote of the Academic Council, Archpriest Vladimir Vorobyov was elected rector of the Theology and Catechism courses.

Based on the Theology and Catechism courses, the St. Tikhon’s Orthodox Theological Institute (PSTBI) was established in 1992. In its early years, Father Gleb Kaleda taught a course on scientific apologetics. In 1995, Alexander Dvorkin took the position of head of the Department of Sectology.

From the official PSTBI website:

“The spiritual and moral revival of the peoples of Russia, and consequently overcoming the general crisis that has engulfed Russia, requires a swift return to the historical spiritual and cultural roots of national and state life, that is, to Orthodoxy. One of the endeavors of national and ecclesiastical significance was the creation of the St. Tikhon’s Orthodox Theological Institute in Moscow. The St. Tikhon’s Orthodox Theological Institute was established with the blessing of His Holiness Patriarch Alexy II of Moscow and All Rus’ in 1992.” 11

PSTGU Rector Archpriest Vladimir Vorobyov recollects:

“I remember a warm conversation with His Holiness the Patriarch. Smiling, he asked me, ‘Do you want to compete with the theological schools?’ I replied that healthy competition is beneficial and would help the development of theological schools as well. He agreed with this and signed our charter.” 12

On the one hand, the creation of such an institute was necessary and met the needs of the time as well as the revival of Orthodoxy immediately after the collapse of the USSR. On the other hand, the Soviet legacy, and consequently the entanglement of KGB structures with the ROC, could not dissipate so quickly. The creation of such an educational platform became a temptation to introduce destructive programs by former KGB operatives.

The institute became a place for shaping a new, “correct” worldview among church clergy and laity. It was here that those who would later become prominent anticultists — essentially, mere inquisitors — began their journey. Later, they would shape the modern ideology of Russian society.

In 2004, the institute was granted the highest accreditation status — a “university” — and has since been known by its modern name, PSTGU.

As of now (2025), PSTGU is the only Orthodox educational institution accredited by the state as a “University.” 13 PSTGU is a full-fledged developer of the state educational standard. It serves as Russia’s theological research forum, one of the largest in the world.

The creation of the institute pursued several objectives 14:

- Training qualified personnel for pastoral service and work in secular structures, including educational and social institutions.

- Pursuing the legalization of theological science and religious education. This included state registration, licensing, and accreditation of church educational institutions with recognition of their diplomas.

- Transition to a university-based educational system and cooperation with foreign theological institutes (including Catholic and Lutheran ones) to improve the quality of theological education. Notably, this includes establishing inter-university communication with institutions where John Meyendorff and Johannes Aagaard worked.

On May 25–27, 1992, the Theological Institute held its first conference, titled “Readings in Memory of Archpriest Vsevolod Spiller,” with active participation from Protopresbyter John Meyendorff. Patriarch Alexy II attended one of the sessions.

From the recollections of PSTGU Rector Archpriest Vladimir Vorobyov:

“Thanks to Father John [Meyendorff] showing us such attention and support, Patriarch Alexy also visited us, gave a speech, and the institute gained a certain recognition in the eyes of the church community.” 12

Based on this conference, the Christmas Readings began in 1993, later transforming into the Annual International Theological Conference. 14

Eventually, these conferences became, among other things, a platform for informational terror attacks and persecution of “wrong” priests and organizations. These readings, beyond everything else, effectively turned into a tool that facilitated the dangerous fusion of church and state, erasing the boundaries between secular authority and religious institutions, thereby threatening the principles of freedom of conscience and the foundations of democracy.

Starting in 1994, when the Christmas Readings had already gathered more than 1,000 attendees, the Minister of Education of the Russian Federation, leaders of the Russian Academy of Education, and the Moscow Committee of Education became regular participants. State educational structures became co-founders of the Christmas Readings. 15 The International Christmas Readings were also frequently held within the walls of the University of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia.

That is how the Russian Orthodox Church actively strengthened its position within state structures.

Visits to Butyrskaya prison

This is how Alexander Dvorkin himself describes the events of 1992 in Moscow. As a reminder, with a letter of recommendation from John Meyendorff, Dvorkin gained access to the newly created sector of religious education in the Synodal Department of Religious Education and Catechism under the leadership of Gleb Kaleda.

“At first, I was in my ‘prison stage’ activity. Let me explain. One day, the choir of the Nikolo-Perervinsky Monastery was invited to Butyrka Prison. The choir members were not monks but laypeople, so they approached us, asking for a ‘secret’ catechist who could, between hymns, explain what they were singing and the meaning behind the lyrics. Ideally, a priest was needed, but at that time, we could not even consider such a thing. Father Gleb sent me. ‘But I can’t sing!’ I said. ‘No problem, just move your mouth,’ Father Gleb told me. However, he later decided to try entering the prison himself, and to his surprise, he was allowed in without any issues. That’s how my prison ministry began: I spent one day a week at Butyrka Prison. This was the first time in Soviet history that a priest had entered a prison voluntarily to talk with inmates and offer them support.” 3

Gleb Kaleda dedicated a great deal of time to the Butyrka Church, where he spiritually guided his challenging congregation — robbers, thieves, and murderers.

Since the resumption of cooperation between the Orthodox Church and correctional institutions in 1990, clergy have been granted the right to visit prisoners and provide spiritual guidance in places of detention. 16 In 1994, the first document formalizing the agreements on joint efforts between the Russian Orthodox Church and the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD) of the Russian Federation was introduced. 17 One of the signatories of the first agreement with the MVD on behalf of the ROC was Metropolitan Kirill (Gundyaev) of Smolensk and Kaliningrad.

It is worth noting that Father Gleb Kaleda developed a strong friendship with Gennady Oreshkin, the head of Butyrka prison. 18 However, the appearance of Alexander Dvorkin, an American layman, in a high-security facility under armed guard, where outsiders are not permitted, raises concerns. It is also concerning that Butyrka prison is located in close proximity to the Main Directorate of Internal Affairs of Moscow. One might wonder, do employees of both institutions dine in the same cafeteria? Understanding the goals of global anticultism in Russia and Dvorkin’s role in them, it becomes clear how gaining the trust of law enforcement could be achieved in this way. This is especially true given Dvorkin’s claim that he visited the prison once a week for an entire year. 19

New Relations with the Armed Forces and Law Enforcement Agencies

Subsequently, in 1995, the ROC established the Synodal Department for Cooperation with the Armed Forces and Law Enforcement Agencies.

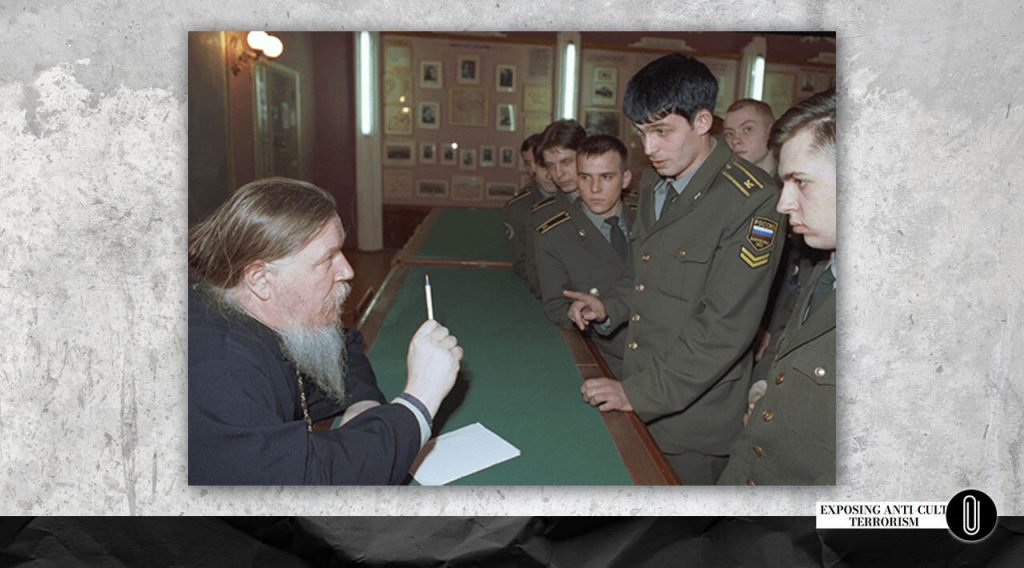

At the time, the Department included a training and methodological center, an information and analytical service, and a sector for special pastoral ministry. The interaction of this new synodal institution with law enforcement and judicial systems was built on agreements signed between the ROC and various security ministries and agencies. In their work, ROC Department staff received assistance and support from the command of the Armed Forces and law enforcement agencies, as well as from officers responsible for educational work.20

From its inception, the leadership of the ROC Department placed special emphasis on training and methodological work. A Center for Spiritual Education of Military Personnel was established at St. Tikhon’s Orthodox Theological University [PSTBU]. 20 Faculties of Orthodox culture were created in some military universities in the capital and other cities across Russia. An important aspect of the Department’s cooperation with the Armed Forces was organizing and conducting joint scientific and practical conferences, which involved both military personnel and priests serving in the army.

A significant part of the Department’s activities over the years has been its cooperation with the Ministry of Justice of the Russian Federation, which currently oversees the Federal Penitentiary Service (FSIN).20

“If I were the director of the Federal Penitentiary Service and were given funding, I would try to make some changes within the budget. When I worked with prisons, I certainly had such a dream. But I understand how difficult it is to turn a prison into a rehabilitative system,” said Archpriest Dmitry Smirnov in an interview with the news portal “Pravoslavie i Mir” (“Orthodoxy and the World”). 21

In 2001, Archpriest Dmitry Smirnov was appointed as the new head of the Department, under whom its key activities continued to develop further 20:

- The Department’s structure was reformed.

- New areas of activity emerged.

- Informational and publishing efforts were intensified.

- Cooperation with law enforcement agencies expanded, especially after the revival of the institution of full-time military chaplaincy in 2009, taking on a more systematic approach.

In 2003, a cooperation agreement was signed between the Ministry of Justice of the Russian Federation and the Russian Orthodox Church.20 It provided for joint efforts in organizing spiritual guidance for employees of the Correctional System (UIS) and inmates, distributing spiritual, moral, and patriotic literature, providing humanitarian aid, and holding lectures on the fundamentals of Orthodoxy.

By 2010, the Synodal Department for Prison Ministry was established.20 Matters concerning the interaction between the Russian Orthodox Church and UIS institutions in various regions of Russia were transferred to the newly formed synodal body.

Currently, the new structure of the Russian Orthodox Church’s Department includes 10 sectors for cooperation with various branches and types of the Armed Forces, as well as troops and military formations that are not part of the Armed Forces. The main sectors are as follows 20:

- Ground Forces

- Russian Navy (VMF)

- Air Force (VVS)

- Strategic Missile Forces (RVSN)

- Aerospace Defense Forces (VKO)

- Airborne Forces (VDV)

- Internal Troops of the Ministry of Internal Affairs (VV MVD)

- Border Service of the FSB of Russia

- Federal Customs Service

- Federal Protective Service

- Sector for cooperation with the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD)

The tasks of the Russian Orthodox Church’s Department also include coordinating and practically implementing pastoral and spiritual educational activities among servicemen, law enforcement officers, and their family members.

Alexander Dvorkin’s personal connections with Archpriest Dmitry Smirnov and his work at Saint Tikhon’s Orthodox University of Humanities allowed him to gain access to the departments of the Russian Armed Forces and law enforcement agencies, where he spread his anticultist and neo-Nazi ideas. In doing so, they violated an order from the Minister of Defense prohibiting foreign citizens from visiting military facilities. 22 Despite this, Dvorkin delivered lectures to servicemen at military units.

Thanks to his “fruitful” work in dehumanizing individuals deemed undesirable by the Russian Orthodox Church, an Expert Council was established for him under the Russian Ministry of Justice in 2009, with Alexander Dvorkin appointed as its chairman.

It is also worth noting that Russia’s Minister of Justice, Alexander Konovalov, is a graduate of Saint Tikhon’s Orthodox University of Humanities. 23 And he is not the only Russian minister with a degree from this institution.

With the appointment of the overtly Orthodox Alexander Konovalov as Minister of Justice in 2008, radical “anti-sect” activists were appointed as the Ministry’s chief religious experts. This led to alarming inspections of religious organizations, and in October 2009, the Russian Ministry of Justice proposed a bill that strictly limited missionary activity in the country. These actions undermined many believers’ trust in the government as a whole, with discussions arising about the beginning of a new wave of religious persecution. 24

Attack on “The Law on Education”

Here’s how the rector of Saint Tikhon’s Orthodox University of Humanities, Archpriest Vladimir Vorobyev, justifies the goals of the “educational reform” and the displacement of secular education in schools:

“Russian legislation is still not free from the influence of Soviet laws. According to the law on freedom of conscience, there is secular education and religious education. Religious education, by definition of the law, aims to prepare clergy, which refers to spiritual schools. All other education is secular. Secular education, in the overwhelming majority of schools in our country, is still based on an atheistic worldview, in accordance with the standard […]” 25

The attack on the “On Education” law began with the creation of a religious standard for theology. The first religious standard for theology was developed at Saint Tikhon’s Institute in 2001, but it was only approved by the state in 2014. Later, we will discuss the significant events that took place during this period.

From the memoirs of Rector of Saint Tikhon’s Orthodox University of Humanities, Archpriest Vladimir Vorobyev:

“Without this standard, licensing theological schools and the recently adopted law on their accreditation would have been impossible. The creation and approval of the state multi-confessional standard for theology is an important milestone in the development of theological education in Russia. Moreover, it is the development of confessional education, not atheistic or agnostic. Our university, it seems, made a significant contribution to overcoming Lenin’s decree ‘On the Separation of Church and State and School from the Church.’” 25

The goal is very simple: to unite the Church and the state in the field of education and eliminate everything secular. To achieve this, theology is being introduced into the academic sphere, gradually replacing secular religious studies.

“Theologians and religious scholars have the same subject of study — religion, but different methodologies. Religious scholars study the subject from the perspectives of history, cultural studies, sociology, anthropology, and use research methods typical for these disciplines. They may doubt the validity of any authoritative opinion, and scientific theories can change for them as quickly as day and night. A theologian is a scholar of theology. He does not question the dogmas formulated at the First and Second Ecumenical Councils.” This distinction between religious studies and theology was described by Oleysa Kuznetsova, assistant professor in the Religious Studies section of the Department of Ontology and Theory of Knowledge at the Ural Federal University. 26

Thus, for an Orthodox theologian, there are certain axioms that cannot be refuted or doubted; these axioms represent truth for him. From this position, he studies other denominations, movements, and religions. In other words, he is subjective and strictly confessional. A religious scholar, on the other hand, is a researcher who approaches from an objective scientific standpoint. He is outside any confession, studying religion from the outside.

Here is the definition of a theologian according to the educational institution “International Academy of Expertise and Evaluation,” which trains theologians:

“A theologian is an expert on religious heritage. He studies the history and philosophy of religion, analyzes historical sources, and evaluates various religious organizations.” 27

“A theologian engages in studying religious worldviews. His activity is related to the explanation and transmission of the principles of Christian philosophy. He studies fundamental systematic theology, apologetics, the theory and practice of worship, as well as church law.” 27

“A theologian can engage in scientific research or teach theology, the history of religions, the foundations of Orthodox culture, or theology in various educational institutions.” 27

“Experts with extensive knowledge and analytical skills can work as security specialists, identifying destructive cults and sects.” 27

From the recollections of the rector of Saint Tikhon’s Orthodox University of Humanities (PSTGU), Father Vladimir Vorobyov:

“When we in the Ministry of Education said that the theology standard, approved by the ministry at the time and written in the context of scientific atheism, was absolutely unacceptable to us because it was a parody of theology, we were told, ‘Write a different standard.’” 25

“This was done, but the ministry was in no hurry to approve the standard, claiming that according to the constitution, our education is secular and this standard allegedly violated the constitution. It took several years to prove that teaching theology and, in general, education based on a religious worldview can be secular, and that ‘secular’ does not necessarily mean ‘atheistic.’ It took a lot of effort and time, but our efforts were successful.” 25

“As a result of this victory, religious education began to develop very rapidly. Today, there are already about fifty theological departments in Russia, with more than half of them established at state universities. The vast majority of them are Orthodox, though there are also Muslim and Jewish ones.” 25

“The standard was the first legitimate act that legalized the cooperation between Church and state. Such cooperation existed earlier in other areas, but it lacked a legal basis. The standard stated that teachers of religious doctrinal subjects should be appointed upon the Church’s recommendation. This means that from now on, the school is not separate from the Church, because religious education without the Church is impossible.” 25

Patriarch of Moscow and all Rus’, Alexy II, in his congratulatory message to the university on its 16th anniversary, highlighted the contributions of PSTGU in the development of spiritual and secular Orthodox education in Russia, specifically its achievements in the adoption of the law on the state accreditation of theological schools and the development of the third-generation state theology standard project.

“Over the years of hard and persistent work, the university has become a forge of personnel for the Russian Orthodox Church,” noted Alexy II. 28

It is worth remembering that it is in this university (PSTGU) that Alexander Dvorkin has been teaching “sectology” for 30 years.

In 2007, an open letter was published by 10 academicians to the President of Russia. This letter was a response to the resolution “On the Development of the Domestic System of Religious Education and Science,” which was adopted at the “XI World Russian People’s Council.”

The World Russian People’s Council (WRPC) is an international public organization founded in May 1993 under the auspices of the Russian Orthodox Church. 29

In this resolution, the Council (WRPC) proposed to address the Government of Russia with a request “to include the specialty ‘theology’ in the list of scientific specialties of the Higher Attestation Commission (VAK) and to preserve theology as an independent field of science.” Moreover, the resolution contains another urgent request “to recognize the cultural significance of teaching the fundamentals of Orthodox culture and ethics in all schools of the country and to include this subject in the corresponding area of the federal educational standard.”

Here’s how one of the authors of the letter, Nobel laureate Vitaly Ginzburg, described it:

“This letter from ten academicians to the president expresses concern about the clericalization of our country – the Church’s takeover of ever-increasing areas of public life.” 30

The letter emphasizes that “The Church’s infiltration into state organs is an obvious violation of the country’s Constitution. However, the Church has already infiltrated the armed forces.” 31

This caused a huge public reaction among church leaders. In this sense, the open letter to the President of Russia became an “information occasion” for discussing these and other issues related to the relationship between the Church and society. Soon, in early 2008, a “response” letter was published by 227 scholars who supported the clericalization of education and saw no problem with it. 32 Journalists noted the rather aggressive rhetoric of the letter, with epithets such as “militant atheists and haters of Russia.” 32 However, the authors of the “response” letter have remained anonymous.

There was an interesting theory circulating online at the time about the authorship of the “response” letter, which we find noteworthy:

“The appeal was initiated by circles close to the Orthodox St. Tikhon’s University. The introduction of Orthodox culture lessons (OPK) in schools, as well as habilitation in ‘theology’ at the doctoral level, which the anonymous authors and signatories of the appeal are likely aiming for, would potentially secure the academic and teaching careers of graduates from this institution. Therefore, a state decision on teaching Orthodox culture lessons and registering ‘theology’ as a specialty with the Higher Attestation Commission (VAK) for PhD and Doctoral dissertations would significantly raise the prestige of PSTGU, which is crucial given the current liberalized state of the educational services market in the country.

It’s no secret that to maintain university status, an institution must prepare specialists (bachelor’s and master’s students) in a wide range of specialties. To avoid losing its university status, PSTGU, for instance, opened a new department in 2008: the faculty of computer science and applied mathematics. But the title of ‘university’ is not just about prestige; it’s also about funding. Additionally, and importantly, it’s about expanding the staffing base, thus broadening the potential labor market for teachers and researchers.” 33

In 2009, as an experiment, the course “Fundamentals of Religious Cultures and Secular Ethics” was introduced in schools in 19 regions of Russia. Within the framework of this course, parents could choose which religion their child would study (taught by secular teachers). By 2012, the experiment was recognized as successful, and from 2012 onward, in accordance with the order of the Ministry of Education and Science of Russia, the subject “Fundamentals of Religious Cultures and Secular Ethics” was included in the school curriculum as a federal component.

In 2013, amendments to the law “On Education” came into force. Now, priests were allowed to teach in schools. 34 Prior to this, religious organizations could only serve as founders of schools, but priests were not allowed to teach there.

According to the new law, parents could still choose whether their child would study “Fundamentals of Secular Ethics” or the basics of one of the religions. However, now religious organizations were granted the right to review the content of the course materials to ensure they aligned with their doctrine, as well as to recommend their own teachers to work in schools. 35

In practice, some regions reported instances of pressure on schools and teachers regarding the teaching of the course “Fundamentals of Religious Cultures and Secular Ethics.” For example, in the town of Khvalynsk, Saratov Region, local authorities took note that only 83% of parents had chosen the module “Fundamentals of Orthodox Culture” (OPK), which was lower than the target of 98%. As a result, the deputy principal of one school, Tatyana Kotserova, was required to write an explanatory note. She was accused of not attending church, celebrating Halloween, and engaging in “anti-Orthodox agitation” among parents. Ultimately, her position was cut. 35

In January 2015, the Higher Attestation Commission of the Ministry of Education and Science of Russia (VAK) approved theology as a new academic specialty. 36

The Fusion of Church and State

The relationship between the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC) and the Russian state has undergone significant changes since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Key events that reflect the process of rapprochement between the Church and the state include:

- 1990: The adoption of the law “On Freedom of Conscience and Religious Organizations,” which recognized citizens’ right to freedom of religion and contributed to the revival of religious life in Russia.

- 1997: The adoption of a new law “On Freedom of Conscience and Religious Associations,” which granted special status to “traditional” religions, including Orthodoxy, Islam, Buddhism, and Judaism, thereby strengthening the role of the ROC in public life.

- 2000: The adoption of the “The Basis of the Social Concept of the Russian Orthodox Church,” which outlined the Church’s views on its interaction with the state and society.

- 2007: The introduction of the “Fundamentals of Orthodox Culture” course into the school curriculum in some regions of Russia, signaling the growing influence of the ROC in the field of education.

- 2010: The creation of the Patriarchal Council for Culture, with the goal of strengthening cooperation between the Church and state institutions in the cultural sphere.

- 2012: Amendments to the law “On Freedom of Conscience and Religious Associations,” strengthening state control over religious organizations and granting additional privileges to the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC).

- 2013: Adoption of the law protecting the feelings of believers, initiated after the incident at Christ the Savior Cathedral, which demonstrated the ROC’s influence on the legislative process.

- 2015: Signing of an agreement between the Ministry of Defense of Russia and the ROC on cooperation, including the construction of churches on military bases and establishing the institution of military clergy.

These events reflect the gradual strengthening of the role of the Russian Orthodox Church in Russia’s social and state life, signaling close interaction between the Church and the state.

“Destructology” — a New Pseudoscience

We have already discussed in other articles that “sectology” is a nonexistent academic discipline that is absent from the current Nomenclature of Specialties for Scientific and Scientific-Pedagogical Workers. 37

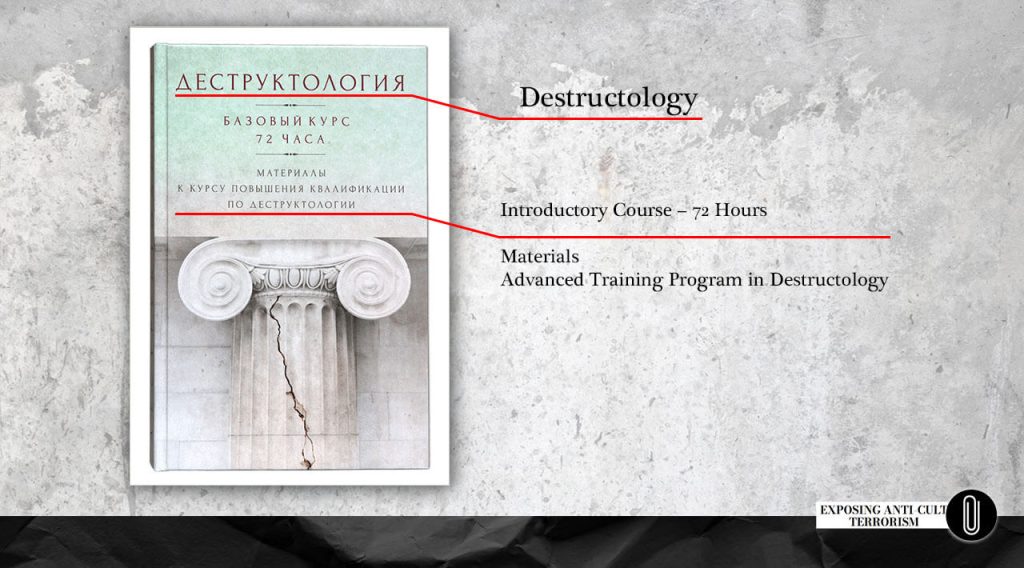

Destructology is a new term for “sectology,” coined by Roman Silantyev, a dedicated supporter of anticultist Alexander Dvorkin.

Silantyev has been a longtime member of RACIRS — the Russian Association of Centers for the Study of Religions and Sects — which Dvorkin founded in 2006.

From 1998 to 2009, he also worked for the Department for External Church Relations of the ROC. 38 He taught at the Department of Theology at Moscow State Linguistic University (MSLU). As an “Orthodox expert” on Islam, Silantyev has repeatedly drawn criticism from the Muslim community and provoked scandals to the point that the ROC leadership was even forced to disown him. 39

In 2009, he became deputy chairman of the Expert Council on State Religious Evaluation under the Russian Ministry of Justice.

It is worth recalling that the election of Dvorkin as chairman of the Expert Council speaks volumes about composition and overall nature of the council: out of its 24 members, only one is a religious scholar — Igor Yablokov, head of the Department of Philosophy of Religion and Religious Studies of Lomonosov Moscow State University. 40 As a result, under the leadership of Dvorkin and Silantyev, the Council earned the nickname “Orthodox Inquisition” for its overt bias.

Professor Ekaterina Elbakyan from the Academy of Labor and Social Relations, described it as follows:

“I was honestly shocked to find that Mr. Dvorkin, who lacks not only personal qualities but also any formal religious studies education, chairs this Expert Council on State Religious Evaluation. Only one member, Igor Yablokov, has a religious studies education. I was, to say the least, extremely surprised.” 41

Remir Lopatkin, religious scholar and professor at the Department of State-Confessional Relations at the Russian Academy of State Service, voiced his stance on such an “expert council.” He stated:

“The act we are witnessing is aimed at discord, at sowing hostility in society, and pitting one part of society against another”. 41

The term “destructology” was first mentioned in Silantyev’s 2018 article, “On Some Theoretical Foundations of Destructology as a New Scientific Discipline,” published in the Moscow State Linguistic University (MSLU) bulletin (Issue 2). The article indicates that destructology, along with “sectology,” aims to combat non-Orthodox and non-traditional movements (both religious and social) and extends its scope to include extremism and terrorism. In the article, Silantyev references sectologist Dvorkin, cult expert Larisa Astakhova, and others.

Under the leadership of Astakhova, who has headed the Department of Theology at MSLU since 2018, destructology has been officially presented as a new “scientific” discipline. Silantyev became a lecturer in this department.

“Some scholars specialize in cults, others in terrorists, and others in preventing teenage suicides, whereas modern challenges require a more universal approach. That is the approach shaped by the new applied discipline of destructology, developed at MSLU. Entire groups of scholars, particularly theologians and religious scholars, will be able to use it to enhance their qualifications and acquire skills to counter destructive threats,” Silantyev explained. 42

This approach fosters public fear of alternative views and strengthens negative attitudes toward any form of religious or ideological freedom.

In 2019, the Laboratory of Destructology was established at MSLU. It was led by Roman Silantyev, while Astakhova, along with several cultologists, joined the laboratory as staff members.

The laboratory’s webpage on the MSLU website states:

“Destructology is a new applied science that comprehensively examines the most dangerous destructive entities: extremist and terrorist organizations, psycho-cults, and non-religious sects; totalitarian sects and the sphere of magical services; suicidal games and hobbies, life-threatening youth subcultures, and medical dissidence”. 43

The first students of the destructology courses were priests and sectologists from Novosibirsk. In 2019, the Novosibirsk Missionary Department’s website published the following news:

“Eleven employees of the Missionary Department of the Novosibirsk Diocese, who completed the training in the ‘Basics of Destructology,’ were awarded certificates from Moscow State Linguistic University for advanced training in higher professional education”. 44

The scientific community considers “destructology” a pseudoscience. 45 In 2023, more than 200 Russian scientists signed an open letter denouncing the pseudoscientific nature of this discipline. They stressed that “destructology” is absent from both Russian and international regulatory frameworks for science and education, and that publications on the topic are essentially limited to the works of Roman Silantyev.

However, this hasn’t stopped the implementation of “destructology” courses in Russian schools, where active work is underway with school principals and teachers.45 Such courses effectively teach participants to identify “destructive” elements in society using extremely vague and subjective criteria. According to the description in the “Cycle of Lectures on Destructology” section on the official MSLU website:

“Modern criminals operate with hellish scale and imagination. This is what researchers of the problem and the authors of the destructology course have come to realize. This new applied science, developed at MSLU, will teach you to distinguish an ordinary service provider from a recruiter for a totalitarian sect.” 46

Then, in 2025, the textbook “Destructology: Basic Course, 72 Hours. Materials for Advanced Training on Destructology,” edited by Roman Silantyev, head of the “destructology laboratory” at MSLU, was set to be published 47 by the Publishing House of the Moscow Patriarchate, which in the 1990s and early 2000s issued the informational and educational magazine “Prozrenie” [“Insight”], dedicated to combating new religious movements and their followers, as well as Dvorkin’s book “Ten Questions for an Intrusive Stranger, or Rules for Those Who Do Not Want to Be Recruited.”

A large part of the textbook is devoted to analyzing the postulates and the “danger of sects and cults” and “destructive religious currents.” Some of Silantyev’s ideas were already detailed in his book titled “Destructology. How to Quickly and Reliably Lose Money and Health. 10 Steps to Success.” In that book, he accused atheists of creating “nonreligious sects” and spreading LGBT; he also criticized movements that promote “racism, xenophobia, and separatism” in Russia, including on the basis of faith and ethnicity. 48

Relying on his “scientific” discipline, Silantyev created the conceptual framework for an expansive interpretation of extremism and terrorism.

Within the framework of “destructology,” he combined such diverse phenomena as religious minorities, youth subcultures, psycho-cults, and even movements promoting “medical dissent.” This allowed him to cast suspicion on a wide range of organizations and groups that do not conform to “traditional values.”

Such an approach effectively enabled any undesirable social phenomenon to be labeled as “destructive” or “dangerous” and allowed laws on extremism to be used to suppress them.

Such “expertise” was used as evidence of “terrorism propaganda” in the case of Evgenia Berkovich and Svetlana Petriychuk, who were tried for a performance about women who joined ISIS. In the summer of 2024, they were sentenced to 6 years in prison. 49

Thus, “destructology” has become a pseudoscientific facade for intensifying repressive measures in Russia. Silantyev, following in Alexander Dvorkin’s footsteps, managed to embed his approach into educational, religious, and law enforcement institutions, which led to a more aggressive use of extremism and terrorism laws against any form of dissent and nonconformity.

Fake Experts

As we know, Dvorkin does not hold any academic degrees recognized by the Russian state’s certification system. 50 However, there is another example: the previously mentioned Larisa Astakhova, who has particularly distinguished herself in the anticult fight against “totalitarian sects.”

Astakhova is a PhD, an associate professor, and a forensic expert in religious studies, sociology, and psychology. She is a longtime acquaintance of Dvorkin and a colleague of Roman Silantyev in “destructology.”

In 2015, Astakhova provided an expert opinion in religious studies on the case concerning the liquidation of the Church of Scientology in Moscow. As an expert, Astakhova represented the autonomous non-profit organization Kazan Interregional Center for Expert Evaluations.

It is worth recalling that on November 23, 2015, the Moscow City Court upheld the claim of the Russian Ministry of Justice to liquidate the religious association Church of Scientology of Moscow. The court ordered the defendant to establish a commission to dismantle the organization within six months.

The Church of Scientology of Moscow was registered as a religious organization on January 25, 1994. In 1997, a new law “On Freedom of Conscience and Religious Associations” was adopted, requiring all established religious organizations to re-register in compliance with the new law’s requirements. This was done specifically to weed out “wrong” religious organizations. Later, the Moscow department of the Ministry of Justice denied the Scientologists re-registration. In July 2015, the Izmailovsky District Court of Moscow ruled that the Ministry of Justice’s refusal to register the Church of Scientology of Moscow as a religious organization was lawful. One of the grounds for the decision was the conclusion of the Expert Council on State Religious Evaluation at the Main Department of the Ministry of Justice of Russia for Moscow, which relied on a forensic expert report in religious studies provided by Larisa Astakhova.

Astakhova’s expert report sparked a heated debate in academic circles — and with good reason.

The imitation of scientific rigor, lack of facts, and absence of logic are just a few of the criticisms experts voiced after reviewing Astakhova’s expert report.

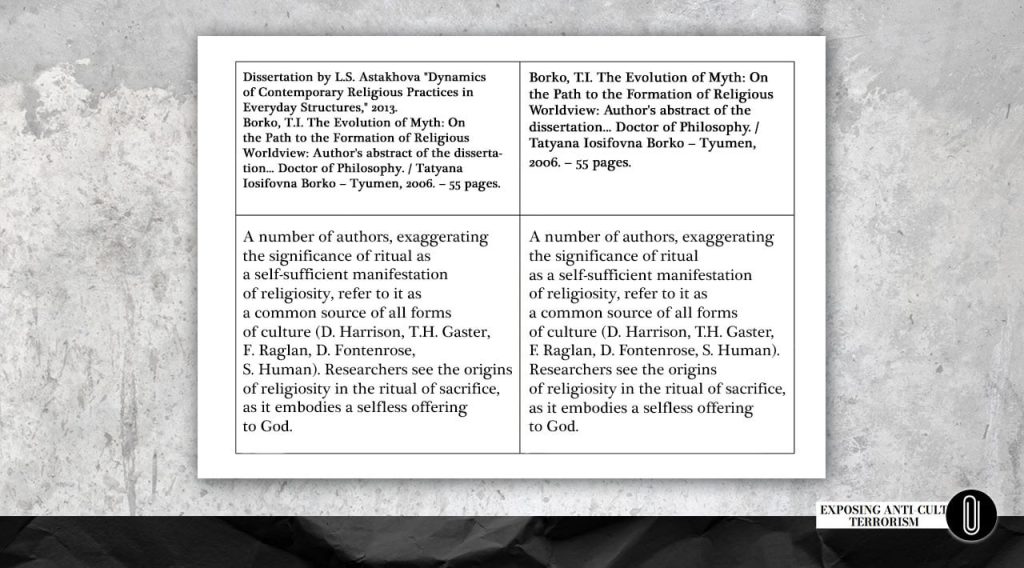

Moreover, in her examination, Astakhova referenced texts from Scientology books that, as it turned out, she simply fabricated! These texts were not only absent from the pages she cited but also from the book as a whole. It’s worth noting that this is a favorite tactic of anticultists. In our analysis of the book “Sectology,” we already caught Dvorkin in blatant lies.

A video recording of the trial, published online, captures the defense’s response. Here is a quote from the court session at the Izmailovsky District Court of Moscow on June 23, 2015:

“The expert has committed an intellectual fraud regarding the objects she examined. We believe that only with deliberate intent can one include in an examination report a quotation allegedly attributed to author L. Ron Hubbard — which, in fact, does not exist in the location the expert indicates, or anywhere else. I’m referring to the quote on page 15 of the expert’s report, which supposedly appears on page 5 of L. Ron Hubbard’s book ‘Introduction to Scientology Ethics,’ from which the expert deduces, no less, the primary aim of the Scientologists.

Now, we reviewed that book — there is no such quote on page 5 or any other page of L. Ron Hubbard’s work. In this case, I don’t know whether the expert invented it or not, but she attributed to the author something he never wrote. In other words, I believe that she has committed an intellectual fraud. It’s the same as if she added a drop of poison while determining the cause of a person’s death and claimed that the person was poisoned. It’s the exact analogous situation.” 51

Many experts have voiced a series of critical comments on Astakhova’s expert report:

- Yuriy Tikhonravov, Candidate of Philosophy, Director of the Center for the Study and Development of Intercultural Relations 52;

- Igor Sorokotyagin, Doctor of Juridical Science, professor, and head of the Department of Legal Psychology and Forensic Examinations at Ural State Law University, Honored Lawyer of Russia 53;

- Galina Shirokalova, Doctor of Social Science, professor, and head of the Department of Philosophy, Sociology, and Political Science at Nizhny Novgorod State Agricultural Academy 54;

- Vladimir Vinokurov, Candidate of Philosophy, associate professor, and deputy head of the Department of Philosophy of Religion and Religious Studies at the Faculty of Philosophy at Moscow State University 55;

- Sergey Shcherbak, Senior Lecturer at the Department of Religious Studies of the Saint Filaret Orthodox Christian Institute 55;

- Nikolay Shaburov, Candidate of Cultural Studies, professor, and Director of the Center for the Study of Religions at RGGU 56;

- Ekaterina Elbakyan, expert in the field of philosophy of religion and religious studies, Doctor of Philosophy, and professor at the Academy of Work and Social Relations 57.

In academic circles, disputes have erupted over Astakhova’s competence as an expert. Nevertheless, the court accepted Larisa Astakhova’s expert report as evidence.

Plagiarism in Larisa Astakhova’s PhD Dissertation: A Threat to Scientific Ethics

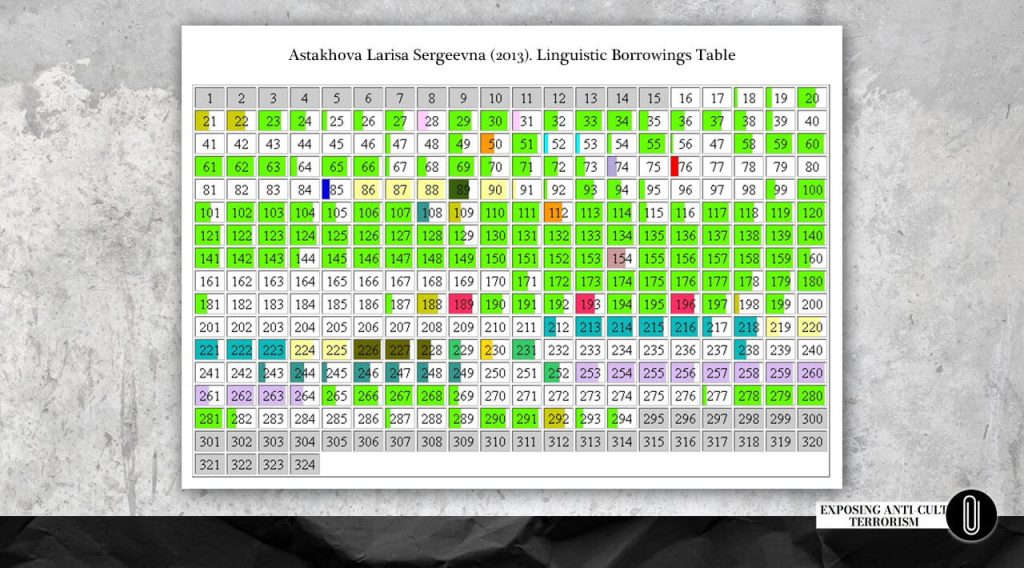

Another scandal arose regarding Astakhova’s PhD thesis. An analysis of the text of her work revealed 55.6% improper borrowings, which is a direct violation of academic standards. 58

On May 30, 2016, a petition was submitted to the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation to revoke Larisa Astakhova’s PhD degree. The petition was accompanied by a 251‐page document containing 252 fragments of borrowings highlighted in color.

According to the expert report submitted by Evgenia Korablyova to the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation, a significant portion of Astakhova’s thesis was borrowed from the scholarly works of other authors without proper citations. Examples include both direct copying and minimal paraphrasing of the authors’ texts. Essentially, her work is a compilation of other people’s ideas, which is unacceptable for a scientific dissertation claiming to earn a doctoral degree. Ideally, such work should be 90% original, with a minimum uniqueness threshold of 70%.

Notably, the same council that approved her thesis was also responsible for reviewing the case to revoke Astakhova’s PhD. According to the Resolution No. 74 of the Higher Attestation Commission (VAK), improper borrowings — even in small numbers — are grounds for revoking an academic degree. Astakhova’s dissertation not only violated these standards but also demonstrated a negligent approach to its review by the Dissertation Council at Pushkin Leningrad State University (LSU), where it was defended.

It is not surprising that the Dissertation Council, despite acknowledging all of Astakhova’s outrageous violations outlined in the Statement, decided not to revoke her PhD — a decision that contradicts the regulatory guidelines.

In an effort to rehabilitate Astakhova in the eyes of the public, a conference titled “Religion and Violence” was held at Kazan State University (KFU) on October 29, 2016.

Astakhova was portrayed as a “martyr” who was harassed by “cultists.” The anticultists resorted to their favorite tactic — accusing anyone who dares to criticize them of being supporters, adherents, or advocates of “cultists.”

“I and some other religious scholars have the impression that the harassment of Larisa Astakhova was orchestrated not only out of a desire to take revenge on her for writing an expert report on the Church of Scientology of Moscow — who supported the position of the Ministry of Justice of the Russian Federation in court to liquidate the organization — but also with the aim of destroying regional centers for religious studies that are gradually becoming strong, powerful, and influential. Naturally, this provokes jealousy among some religious scholars in Moscow and St. Petersburg who have repeatedly expressed their desire for a monopoly in religious studies education,” said Rais Suleymanov, adding that if the academic violence against Astakhova achieves its goal and “breaks” her, then it will be possible to eliminate (or “optimize”) the Department of Religious Studies at Kazan Federal University, followed by a gradual “cleanup” of regional centers for religious studies, or rather their “amputation”. 59

Why is Kazan Federal University (KFU) significant in this case? Because until 2018, Astakhova headed the Department of Religious Studies at KFU. Following this incident, KFU’s administration decided not to renew Astakhova’s contract and those of several of her colleagues. 60 However, Vladimir Rogatin, a member of RACIRS and one of the instigators of the conflict in Ukraine, worked and continues to work in that department. (You can learn more about this in “The IMPACT” documentary.)

In this way, anticultists manipulate facts to intimidate their colleagues and readers, carrying out an informational terror attack. “If they deal with us, you’ll be next!” is the message they try to instill in their colleagues, even though they themselves are the ones engaging in persecution and harassment.

“Dogs of the Lord”

On one hand, it might seem that anticultist Dvorkin is merely a servant of the ROC, simply doing his job, as he puts it — acting as a “sanitation worker” who is cleansing society of “totalitarian sects.” 61 However, a closer examination of his work over the years reveals a clear strategy and a specific goal: controlling public consciousness through education, media, and law enforcement agencies.

In this model of “Dvorkin-style” Orthodoxy, there is no Jesus’ humanism, no His Gospel; instead, there is a rigid vertical hierarchy of patriarchal authority and Church Tradition. Dvorkin’s logic is simple; there’s how he explains it in his article:

“‘The early Church was not deficient, yet it lived without a written Gospel. The written Gospel is not the main thing. So what is the main thing then? What was in the Church, which did not yet have the written Gospel? It lived by Tradition — which in Greek is paradosis and in Latin traditia.” 62

He then reduces all Tradition to the Eucharist:

“How was Tradition manifested? Primarily in the Eucharist. If we look at the first historical book of the Church — the Acts of the Apostles — we see that throughout that book, the Eucharist is mentioned as a recurring theme: epi to auto in Greek. This is a term from early Christian writings with a very specific meaning: a Eucharistic gathering — literally, those words mean ‘for the same purpose,’ that is, a gathering for the Lord’s Supper.” 62

Definition of the Eucharist from the Orthodox website “azbyka.ru”:

“Eucharist (from the Greek εὐχαριστία, meaning thanksgiving or giving thanks) is a Church Sacrament, during which bread and wine are transformed into the True Body and True Blood of Jesus Christ, after which this Body and Blood are consumed by believers (in the form of bread and wine) for the forgiveness of sins and eternal life (John 6:48–54). Giving thanks to God constitutes the main content of this service.” 63

Furthermore, in his article, Dvorkin accuses his opponent of being a “bad Christian” because he needs the Gospel:

“St. John Chrysostom speaks of this when addressing his flock: ‘Since you are bad Christians, you need a Gospel that is written with a reed on parchment or with a quill on papyrus. If you were good Christians, every Gospel word would be written in your heart, and you would need nothing more.’” 62

And this is his way of proving his point—by belittling and demeaning his opponent and provoking emotional responses in readers. In his “expert” articles, Dvorkin readily makes categorical statements, especially against those who do not consider this sacrament to be the most important thing Jesus has brought us: “If anyone thinks otherwise, they are not a Christian.” 64

There is only Dvorkin’s “correct” opinion and the “incorrect” opinion of his opponent. And in this case, it’s easy to label the opponent a “cultist.”

“Therefore, when sectarians deny Tradition, they must reject Scripture as well, because Scripture cannot exist without Tradition. Scripture is a part of Tradition.” 62

This is exactly what the Nazis did in Germany when they dehumanized targeted groups, under the guidance of the Protestant pastor Walter Künneth.

Over 30 years, Dvorkin has built his empire of power. Archpriest Dmitry Smirnov, Archpriest Alexander Novopashin, Roman Silantyev, Larisa Astakhova, Priest Lev Semyonov, and many others are the people Dvorkin has surrounded himself with: authoritarian, despotic individuals with an insatiable lust for power, perfect “henchmen.” This is what Dvorkin exploits and manipulates, carrying out informational and physical terror attacks in society through their hands.

History provides numerous examples of seemingly weak and unremarkable individuals who turn out to be outstanding strategists and manipulators. They used networks of subordinates to carry out the dirty work. While they themselves did not physically participate in crimes, their intellect and cunning directed the actions of others. Modern organized crime is built on the same principle.

Recently, on air, Deacon Andrey Kuraev — who served as an advisor for Patriarch Alexy II from 1990 to 1993 — drew attention to the shift in Patriarch Kirill’s ideology over the past 30 years.

“If you look at his [Patriarch Kirill’s] records, his conversations from the early 1990s — ‘What a liberal metropolitan he was, how wonderfully he spoke.’ And now, he says the exact opposite — calling humanism heresy.” 65

Kuraev then explains this strange behavior of the patriarch:

“As a professional advisor, I’ll tell you, the highest skill for any advisor is to make the thoughts you’ve planted in your boss’s head seem like their own — their own creative idea.” 65

Conclusion

For over 30 years, Dvorkin has been carrying out his informational terror attacks in society, branding all “undesirable” organizations as “totalitarian sects” and intimidating the population. Yet during that time, he himself has created the largest and most terrifying totalitarian sect of all. And this is not merely a criminal intelligence network. He has penetrated the very “heart” of Russia — the Russian Orthodox Church — subjugated power in Russia, and ultimately achieved what was impossible at the dawn of democracy in 1990: the merging of state and Church in Russia.

Of course, this was advantageous for church officials who tasted freedom after the collapse of the totalitarian atheistic regime. This was precisely Dvorkin’s plan.

In this way, he created what he himself calls a totalitarian sect in the literal sense of the word. By destroying Christianity, he acted like the golden calf, seducing the clergy with power through manipulation, destroying the foundations of the state, and imposing true Nazism. With this poison of Nazism, Dvorkin has poisoned Russia, poisoned the Church, created a cult, and dragged everyone into it. His cunning is in the fact that he has created Nazism in a country that suffered from it during World War II the most.

We have repeatedly stated in our articles that the ideology of Nazism never disappeared after World War II. The Nazi ideology is alive. It was passed down from Nazi Protestant pastor Walter Künneth to his follower, Protestant pastor Friedrich Haack. It was Haack, together with Protestant pastor Johannes Aagaard, who wove a vast anticult network across the world. These Nazis accumulated vast experience and knowledge, which they later passed on to Alexander Dvorkin.

A telling example was the 1997 trial in Russia, where Dvorkin, accused of slander and dehumanization, used materials and knowledge accumulated by Aagaard for his defense, explaining to the court that he had not invented anything himself but that it was all “reliable” information from “authoritative” foreign sources. He won the case, and afterward, a new law “On Freedom of Conscience and Religious Associations” was adopted, restricting the activities of New Religious Movements (NRMs).

It is worth recalling that Global anticultism plans its strategies years ahead, orchestrating all wars. And Russia is the country in their game that was meant to become the ideological center of the new Fourth Reich. And they succeeded.

In the following parts of this article, we will explain how dehumanization, branding, guilt by association, and the suppression of dissent operate within the Russian Orthodox Church. To be continued.

Sources:

1. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6J2FTrGdWk

2. https://nasledie.pravda.ru/32395-dvorkin/

3. https://ruskline.ru/monitoring_smi/2015/08/21/aleksandr_dvorkin_v_rossii_udalos_sozdat_protivosektantskoe_dvizhenie

4. https://iriney.ru/main/o-czentre/oficzialnaya-biografiya-a.-l.-dvorkina.html

5. https://mirotver.ru/ofitsialno/svedeniya-o-tserkvi/79-k-istorii-bogorodichnogo-dvizheniya.html