In the late 20th century, anticult influence was firmly rooted in the government structures of France, but the country repeatedly made attempts to weaken it over time. Examples collected in the study by lawyer Patricia Duval, “FECRIS and its Affiliates in France” 1, indicate how difficult it was to maintain balance between the pressure of anticult organizations and the protection of religious freedoms.

The use of any “sect blacklists” was condemned by the French Prime Minister Jean-Pierre Raffarin in a decree dated May 27, 2005 2. It specifically stated: “Experience has shown that the government policy, by which certain groups were characterized as “sects” and the actions of the authorities towards them were based solely on this characteristic, contradicted civil liberties and the secular nature of the state.” The Prime Minister instructed government officials to stop stigmatizing certain groups, but to be vigilant towards all suspicious organizations in order to identify and suppress any criminal or illegal actions.

After a visit to France on September 18-29, 2005, Asma Jahangir, the UN Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief, provided a number of specific recommendations on this subject 3.

Addendum 2 to her report, dated March 8, 2006 4, stated:

“112. The Special Rapporteur urges the Government to ensure that its mechanisms for dealing with these religious groups or communities of belief deliver a message based on tolerance, freedom of religion or belief and on the principle that no one can be judged for his actions other than through the appropriate judicial channels.

113. Moreover, she recommends that the Government monitor more closely preventive actions and campaigns that are conducted throughout the country by private initiatives or Government-sponsored organizations, in particular within the school system in order to avoid children of members of these groups being negatively affected.

114. She urges judicial and conflict resolution mechanisms to no longer refer to, or use, the list published by Parliament in 1996.”

Despite these recommendations on tolerance, the anticult organizations UNADFI and ADFI, funded by the French government, continued to use lists of sects or compile dossiers in order to pin humiliating labels on small religions or beliefs. The situation was aggravated by numerous facts of defamation.

Hate speech and hate crimes

In 1996, Catherine Picard, then president of ADFI North who later became UNADFI president, made very serious accusations against Jehovah’s Witnesses on local radio, calling them “supporters of slave owners,” “drug dealers,” and “pimps.”

On July 18, 2007, the Rouen Court of Appeal decided that UNADFI president was guilty of defamation against Jehovah’s Witnesses 1:

“Undoubtedly, Catherine Picard, by assimilating the movement of the Jehovah’s Witnesses to a mafia movement, by imputing them embezzlement of legacies and donations, by accusing them of organizing under the cover of the spiritual adherence of their members a ‘disguised work’ evoking undeclared employment, which has occasioned criminal prosecutions, has in an outrageous manner and through a fallacious presentation discredited the Jehovah’s Witnesses and thereby had excessive words exceeding the limits admissible for free opinion and exclusive of good faith.

On 3 April 2007, the Court of Cassation found defamatory the statements which were made by Catherine Picard, then Member of Parliament, and Anne Fournier, member of the former Interministerial Mission of Fight against Sects (MILS), against AMORC association (Rosicrucian), in their book ‘Sects, Democracy and Globalization’: Whereas, in order to reject this claim, the Court of Appeals stated, concerning the reported statements from the book, that […] they referred to AMORC not more than to other sectarian movements and expressed generalities on the nature and the functioning of sects and that this being a general opinion, it was wrongly claimed that these excerpts were defamatory.

Whereas in so deciding, when the reported statements — which compared sects to ‘totalitarian groups’, to ‘Nazism’ or ‘Stalinism’, accused them of obtaining by force the adherence of their followers, on whom they exert means of pressure of such nature that they lose their free will, of creating ‘out-law areas’, comparing them to Mafia, — being susceptible of proof and to open debate, are defamatory to all the movements labeled as sects and therefore to the AMORC association, since it stems from the incriminated book that it is one of them, the Court of Appeals has violated the aforementioned provisions of the law.”

In his Report of December 15, 2010, to the sixteenth session of the Human Rights Council (A/HRC/16/53), Heiner Bielefeldt, the UN Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief and successor of Asma Jahangir, stated 1:

“Indeed, in many countries members of religious or belief minorities experience a shocking degree of public resentment or even hatred which is often nourished by a paradoxical combination of fear and contempt. Even tiny groups are sometimes portrayed as ‘dangerous’ because they are alleged to undermine the social cohesion of the nation, due to some mysteriously ‘infectious’ effects attributed to them. Such allegations can escalate into fully fledged conspiracy theories fabricated by competing groups, the media or even state authorities. At the same time, members of religious or belief minorities are often exposed to public contempt based, for instance, on rumors that they allegedly lack any moral values.

It is exactly this combination of demonizing conspiracy projections and public contempt that typically triggers violence either directed against members of minorities or occurring between different communities. Hence the eradication of stereotypes and prejudices that constitute the root causes of fear, resentment and hatred is the most important contribution to preventing violence and concomitant human rights abuses.” (§29)

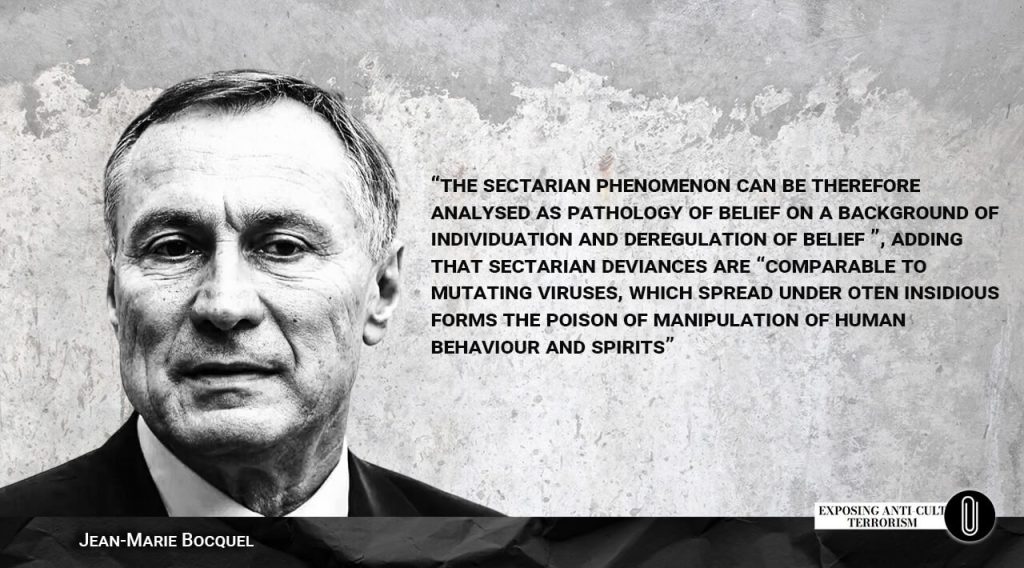

Demonization is pretty obvious in the above examples of defamation. The expression “infectious effects” mentioned by the UN Special Rapporteur is quite accurate in light of some public statements made by French officials. At the first national conference organized by MIVILUDES at the City Hall of Lyon on November 26, 2009, the French Secretary of State for Justice, Jean-Marie Bocquel, gave a speech where he said that “The sectarian phenomenon can be therefore analyzed as pathology of belief on a background of individuation and deregulation of belief”, adding that sectarian deviances are “comparable to mutating viruses, which spread under often insidious forms the poison of manipulation of human behavior and spirits.”

Declaring publicly that sectarian deviances are an infection while government funded anti-sect associations stigmatize specific religious or belief minorities as “sectarian” can only fuel fear, resentment and hatred in the public towards these groups, as explained by the UN Special Rapporteur.

As a matter of fact, the Jehovah’s Witnesses provide very alarming figures of incidents of violence against their members or their places of worship in France. A survey they did throughout Europe showed that France was the European country where they recorded the highest number of hate incidents in 2008-2009, against their places of worship or their members: there have been 149 incidents altogether in that period of time, including 130 acts of vandalism, 12 burglaries or thefts, 5 arson attacks, and 2 threats or assaults.

Hate crime

The OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights provides the following definition of a hate crime on its website 5:

“A hate crime is a crime that is motivated by intolerance towards a certain group within society. For a criminal act to qualify as a hate crime, it must meet two criteria:

- The act must be a crime under the criminal code of the legal jurisdiction in which it is committed;

- The crime must have been committed with a bias motivation.

‘Bias motivation’ means that the perpetrator chose the target of the crime on the basis of protected characteristics.

A ‘protected characteristic’ is a fundamental or core characteristic that is shared by a group, such as ‘race’, religion, ethnicity, language or sexual orientation.

The target of a hate crime may be a person, people or property associated with a group that shares a protected characteristic.”

The above-mentioned actions against Jehovah’s Witnesses and their property, as well as actions aimed against other religious minorities in France, were and continue to be motivated by hate and prejudice, the reason for which is that FECRIS affiliates stigmatize these minorities as “sects” — a label that is used to mean “deviant from the prevailing ideology.”

This equally applies to other anticult organizations, including RACIRS.

Organizations such as FECRIS and RACIRS, supported by government funding, are often criticized for actions contradicting the principles of freedom of religion and belief enshrined in the national constitutions and international human rights acts. Actions of these organizations look more like an ideological conquest and a principled confrontation rather than an objective analysis, which raises doubts about the validity of their powers.

Examining the cases of “sects” and “cults” indicates that often the so-called “victims” in those cases are people who voluntarily decided to join a certain movement for religious or philosophical beliefs. Even though their relatives are unwilling to accept such decisions, people should have the right to believe or not to believe, and this right deserves due respect.

FECRIS and its French branches are often criticized for actions aimed at discriminating and stigmatizing religious minorities without conducting real dialogue, which goes against the UN recommendations on tolerance and dialogue.

Sources:

1. Patricia Duval. “FECRIS and its Affiliates in France. The French Fight against the ‘Capture of Souls’” http://www.hrwf.net/images/reports/2012/2012fecrisbook.pdf

2. https://politique.pappers.fr/document/circulaire-27-mai-2005-relative-lutte-contre-derives-sectaires-JORFTEXT000000809117

3. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/565819?ln=en&v=pdf

4. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/570722?ln=en&v=pdf

5.http://web.archive.org/web/20130416160434/http://www.osce.org/odihr/66388